Translate this page into:

Teenage pregnancy and its predictors in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis

Address for correspondence: Addis Eyeberu, School of Nursing and Midwifery, College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, Harar, Ethiopia. E-mail: addis7373@gmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Qassim Uninversity and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

Although teenage pregnancy has declined in the last decade, it remains a major public health issue in Africa. Maternal mortality is common among teenagers due to their increased risk of obstetric and medical complications. In Africa, there is a lack of robust and comprehensive data on the prevalence and predictors of teenage pregnancy. As a result, this systematic review and meta-analysis were carried out to summarize evidence that will assist concerned entities in identifying existing gaps and proposing strategies to reduce teenage pregnancy in Africa.

Methods:

The review is registered by the international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42021275013). This search included all published and unpublished observational studies written in English between August 23, 2016, and August 23, 2021. The articles were searched using databases (PubMed, CINHAL [EBSCO], EMBASE, POPLINE, Google Scholar, DOAJ, Web of Sciences, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, and SCOPUS). Data synthesis and statistical analysis were conducted using STATA version 14 software. Forest plots were used to present the pooled prevalence and odds ratio (OR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI) of meta-analysis using the random effect model.

Results:

A total of 43,758 teenagers (aged 13–19) were included in 23 studies. In Africa, the overall pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy was 30% (95% CI: 17–43). Western Africa had the highest prevalence of teenage pregnancy 33% (95% CI: 10–55). Age (18–19) (OR = 2.99 [95% CI = 1.124–7.927]), wealth index (OR = 1.84 [95% CI = 1.384–2.433]), and marital status (OR = 6.02 [95% CI = 2.348–15.43]) were predictors of teenage pregnancy in Africa.

Conclusion:

In Africa, nearly one-third of teenagers become pregnant. Teenage pregnancy was predicted by age (18–19), wealth index, and marital status. Strengthening interventions aimed at increasing teenagers’ economic independence, reducing child marriage, and increasing contraceptive use among married teenagers can help to prevent teenage pregnancy.

Keywords

Africa

meta-analysis

predictors

systematic review

Teenage pregnancy

Introduction

Teenage pregnancy is the occurrence of pregnancy within the ages of 13–19 years.[1] It is a global health issue that bears many sequelae of serious health, and social and economic problems for individuals, families, and communities.[2] Every year, approximately 21 million girls aged 15–19 years living in the developing countries become pregnant; nearly half of all teenage pregnancies are unintended, and more than half end in abortion.[3] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also reported that among mothers aged 15–19 in the US, 72.7% reported that they had an unintended pregnancy that resulted in a live birth.[4]

Teenage pregnancy is a major health issue in Africa. Even though teenage pregnancy has declined in the past few decades, it remains a health concern and priority for many African countries. There are few studies assessing the overall burden of teen pregnancy in African countries. Those that have been conducted showed that the prevalence of teen pregnancy was between 18% in Kenya to 29% in Malawi and Zambia.[5] Further, a study done in South Africa found that nearly half of female teens in Africa experienced an unintended pregnancy, with 26.3% of those unintended pregnancies ending in abortions.[6]

Teenage pregnancy is related to maternal mortality and morbidity. A study done in Nigeria showed that 33% of maternal mortality attributes to teenage pregnancy.[7] Teenagers faced a higher risk for eclampsia, anemia, hemorrhage, cephalopelvic disproportion, prolonged labor, and cesarean section.[8] Teenagers are also more likely to develop obstetrical and medical complications such as preterm deliveries, iron deficiency anemia, and perineal tears.[9] It is suggested that increasing contraceptive use can prevent unwanted teenage pregnancies.[10] However, less than half (44.7%) of teenage mothers aged 15–19 who had an unintended pregnancy reported using contraception.[3] Similarly, contraceptive use remained low in Sub-Saharan Africa (18.87%).[11] In Nigeria, less than half (45.3%) of sexually active teenage girls used a modern contraceptive method.[12] Contraception is used by 31.8% of Ethiopian teenagers.[13] Meeting the unmet need for modern contraception among teenagers would prevent 6 million unintended pregnancies per year, averting 2.1 million unplanned births, 3.2 million abortions, and 5600 maternal deaths.[3]

Teenage pregnancy is also associated with perinatal health issues. Teenage mothers developed more adverse perinatal complications, such as preterm births, stillbirths, neonatal deaths, and delivered low birth weight babies.[14,15] Newborns born to teen mothers were admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit due to low birth weight, sepsis, respiratory distress syndrome, hyperbilirubinemia, and asphyxia.[11-13,16] Teenage pregnancy is needed to be tackled to prevent perinatal health issues.

Preventing teenage pregnancies is Africa’s top priority. Investing in teenagers’ health allows them to grow into healthy adults who can contribute positively to society. It is critical to reduce the burden of teenage pregnancies in the developing countries to reduce its sequels. As a result, reducing and preventing teenage pregnancies are a key component of sustainable development goal 3.[17] Furthermore, African countries such as Ethiopia have several policies aimed at improving adolescent health and preventing teen pregnancy.

Identifying the predictors of teenage pregnancy is important for planning appropriate intervention. Even though there are related studies conducted in Africa, they are inconsistent and not inclusive that illustrating the full degree of the larger impact. Furthermore, they are not recent pieces of evidence[18-20] and they did not use meta-analysis methods to pool the prevalence and predictors of teenage pregnancy.[18,19,21] Therefore, this systematic review and meta-analysis aimed to estimate the pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy and summarize the predictors of teenage pregnancy in Africa. The summarized evidence obtained from this study could help interested entities to identify existing gaps and propose strategies to reduce teenage pregnancy in Africa.

Methods

Protocol and registration

This review was based on the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guideline [Additional File 1].[22] The review is registered by the international prospective register of systematic reviews (CRD42021275013).

Eligibility criteria

Articles that met the following inclusion criteria were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. (i) Study design: Observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies); (ii) populations: Teen girls (13–19 years) residing in one of the countries in Africa; (iii) study setting: Institutional or community-based studies in rural or urban settings in Africa; (iv) language: Studies published in English; and (v) time: Studies published in the selected databases between August 23, 2016, and August 23, 2021. The duration of the study was 5 years.

Studies published before August 23, 2016, interventional studies, reviews, commentaries, editorials, case series/reports, conference abstracts, personal opinions, non-teenage participants, and patient stories were excluded from the study.

Information sources and search strategy

Published articles were searched on the major databases (namely, PubMed, CINHAL (EBSCO), EMBASE, POPLINE, Google Scholar, DOAJ, Web of Sciences, MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, SCOPUS, Joanna Briggs Institute EBP (JBI EBP), Global Index Medicus, African journals online, Google search, and MedNar) using a combination of Boolean logic operators (AND, odds ratio (OR), and NOT), Medical Subject Headings (MeSH), and keywords.

The articles were searched using a combination of search terms (AND, OR, and NOT) Boolean (Search) operators. The search strategy includes (“teenage pregnancy “[Title/Abstract] AND “Africa “[MeSH Terms]), (“teenage pregnancy “[exactly on title] AND “Africa “[any field]), and (“teenage pregnancy “[all field] AND “Africa “[all filed]). Non-electronic sources are used combined with a direct Google search, Google Scholar, and MedNar. The search was also conducted by combining the aforementioned search terms with the names of all African countries. Furthermore, the investigators manually searched for gray literature and other relevant data sources such as email and unpublished thesis/papers with planned coverage dates. The CINHAL search strategy is outlined in Additional File 2.

Then, across all databases, all identified keywords and index terms were checked. Finally, all identified articles’ reference lists were searched for further articles.

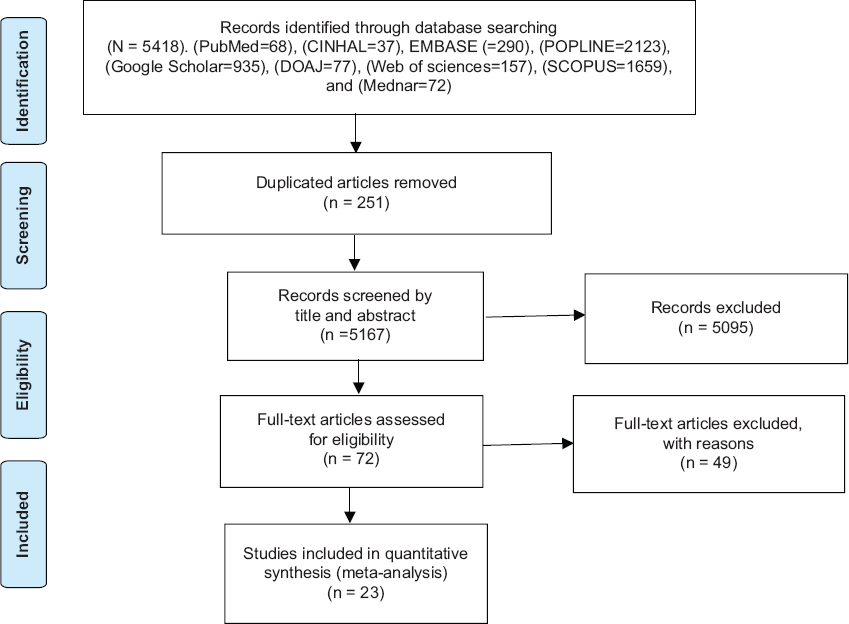

Study selection

All search articles were exported to the EndNote X8 citation manager and duplicate studies were excluded. Then, these were screened carefully by reading the title and abstract. The authors (AE, TG, AS, and MS) screened the titles and abstracts of the identified articles using the eligibility criteria. Then, the full-text articles available in English were further evaluated based on objectives, methods, population, and key findings (prevalence/magnitude and predictors/determinants/factors associated with teenage pregnancy). The overall study selection process is presented using the PRISMA statement flow diagram[23] [Figure 1].

- PRISMA flow diagram shows the selection process of included articles for systematic review and meta-analysis

Data extraction

After the selection of appropriate articles, the authors (AE, TG, AS, MS, YB, AA, and AD) independently extracted the data. A pre-defined Microsoft Excel 2016 format was used to extract the data from selected studies under the following heading: Author and year, region, country of study, setting, study design, sample size, study subject, data collection methods, the primary outcome of interest, and predictors of teenage pregnancy. The accuracy of the data extraction was verified by comparing the results of the two independent extracted data.

The quantitative data (the total sample size (N) and the frequency of the event (n) (number of teenagers who were pregnant), and effect size of predictors of teenage pregnancy) were extracted from the included articles and summarized using Microsoft Excel 2016 for meta-analysis and synthesis.

Measurement and data items

Teenage pregnancy is measured as the “percentage of women aged 13–19 who have given birth or are pregnant with their first child.”[24-31] The prevalence of teenage pregnancy can also be measured as the percentage of pregnant teen women from all women in institutions,[32] who attended health institutions for delivery services[15,33] or antenatal care services[34] during a specific period. Therefore, this review included all studies which used either of the above definitions.

The wealth index is a composite measure of a household’s cumulative living standard. It is calculated using easy-to-collect data on a household’s ownership of selected assets, such as televisions and bicycles; materials used for housing construction; and types of water access and sanitation facilities.[35-37] The wealth index is categorized as low versus high.

Residency is referred to as a place in which a teenager resides. It was classified as rural versus urban. Teenagers who had a history of marital status are categorized as ever married versus not married. Teenagers currently married or divorced or previously married or separated were categorized as ever married. Family planning utilization is also classified as contraceptive user versus contraceptive nonuser.

Educational status is defined as the status of teenagers in education or training defined in law or legislation. It was classified as having no education, completed primary education, completed secondary education, and completed college and above education.

Risk of bias

The authors critically evaluated the risk of bias from individual studies. To minimize the risk of bias, a comprehensive search (electronic/database search and manual search) for published, unpublished, institutional, or community-based studies was carried out. The authors work cooperatively to reduce bias. All worked together in setting a schedule for the selection of articles based on the clear objectives and eligibility criteria, deciding the quality of the articles, regularly evaluating the review process, and extracting and compiling the data. Bias was explored using different statistical tests.[38]

The methodological reputability and quality of the findings of the included studies were critically evaluated using the quality assessment tool for observational studies (cross-sectional, case–control, and cohort studies) developed by the Joanna Briggs Institute.[39] The two groups of authors, Group 1 (TG, AS, AD, and MS) and Group 2 (AE, AA, and YB), independently evaluated the quality of the studies. The mean score of the two groups was taken for a final decision. The differences in the inclusion of the studies were resolved by consensus. The included studies were evaluated against each indicator of the tool and categorized as high, moderate, and low quality. A high-quality score is above 80%, moderate-quality is 60–80%, and low-quality is below 60%. Studies with a score greater than or equal to 60% were included. This critical appraisal was conducted to assess the internal validity (systematic error) and external validity (generalizability) of the studies and to reduce the risk of biases [Additional File 3].

Statistical analysis

Data synthesis and statistical analysis were conducted using STATA 14 software. Forest plots were used to show the prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa. The random effect model of analysis was adopted as a method of meta-analysis because it reduces the heterogeneity of included studies. Subgroup analyses were also conducted by different study characteristics such as sub-regions of Africa (Northern, West, East, South, and Central Africa), study type (community based or institution based), and publication year. Moreover, the meta-analysis regression was conducted to identify the sources of heterogeneity among studies. The predictors of teenage pregnancy were presented using ORs with a 95% confidence interval (CI).

A meta-analysis of observational studies was carried out, based on the recommendations of the I² statistic described by Higgins and Thompson (an I² of 75/100% and above suggesting considerable heterogeneity).[40] P-value for I2 statistics <0.05 was used to determine the presence of heterogeneity.

The investigators checked for potential publication bias through visual inspection of a funnel plot and Egger’s regression test. Publication bias was assumed for P < 0.05. The results of the review were reported according to the PRISMA guidelines. The findings of the included studies were first presented using a narrative synthesis and followed by a meta-analysis chart.

Results

Description of review studies

A total of articles 5418 were identified through the major medical and health electronic databases and other relevant sources. From all identified studies, 251 articles were removed due to duplication while 5167 studies were reserved for further screening. Of these, 5095 were excluded after being screened according to titles and abstracts. Of the 72 remaining articles, 49 studies were excluded due to studies did not present the outcome of interest, being qualitative studies, and non-teenage populations. Finally, 23 studies that fulfilled the eligibility criteria were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis [Figure 1].

Characteristics of included studies

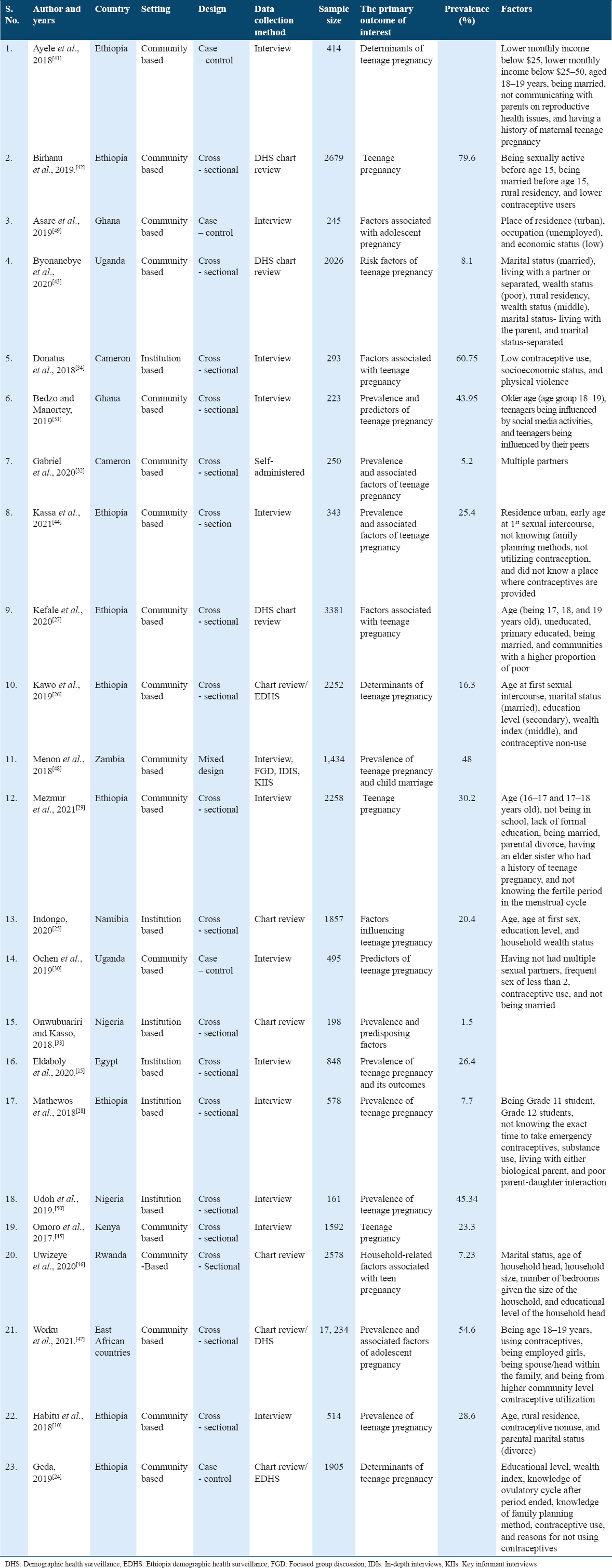

Of all studies, more than half 14 (60.9%) of studies were from East Africa.[10,24,26-30,41-48] Seven studies were from West Africa,[32-34,48-51] one study from North Africa,[15] and one study from South Africa.[25] The majority 18 (78.3%) of the included studies were cross-sectional studies,[10,15,25-29,32-34,42-47,50,51] while four studies were case–control studies[24,30,41,49] and one study was a mixed study.[48] The sample size of the included studies ranged from a minimum of 161 in a study conducted in Nigeria[50] to a maximum of 17,234 in a study conducted in East African countries.[47] A total of 43,758 teenagers (13–19 years) were included in the 23 studies. Thirteen of the included studies reported both prevalence and predictors of teenage pregnancy.[10,25,26,28,29,32,34,42-44,46,47,51] Five studies reported only the prevalence of teenage pregnancy[15,33,45,48,50] and the other five studies only report the predictors of teenage pregnancy.[24,27,30,41,49] The general characteristics of the studies selected for the meta-analysis are outlined in Table 1.

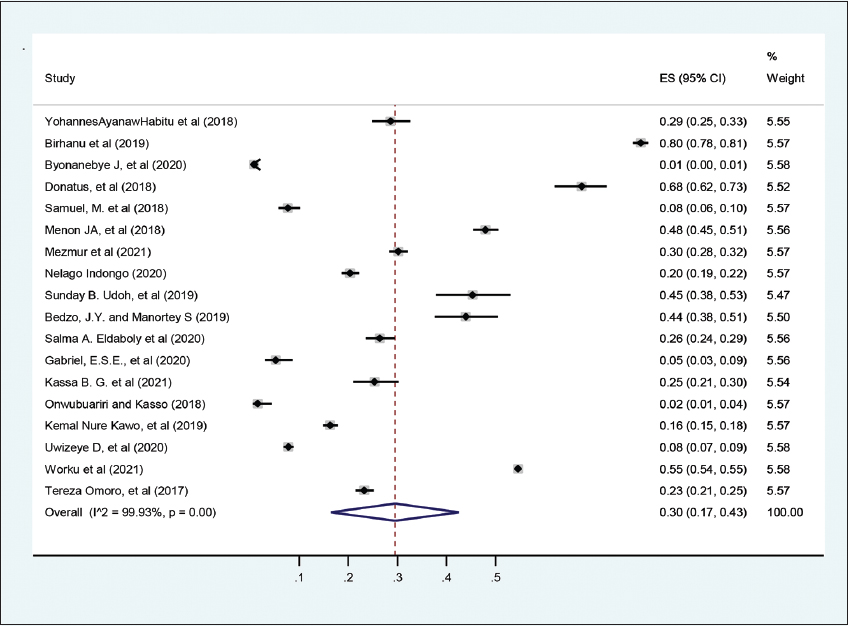

Prevalence of teenage pregnancy

The pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy ranged from 1% to 80% in studies done in Uganda and Ethiopia, respectively.[42,43] The overall pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa was 30% (95% CI: 17–43) [Figure 2].

- The pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

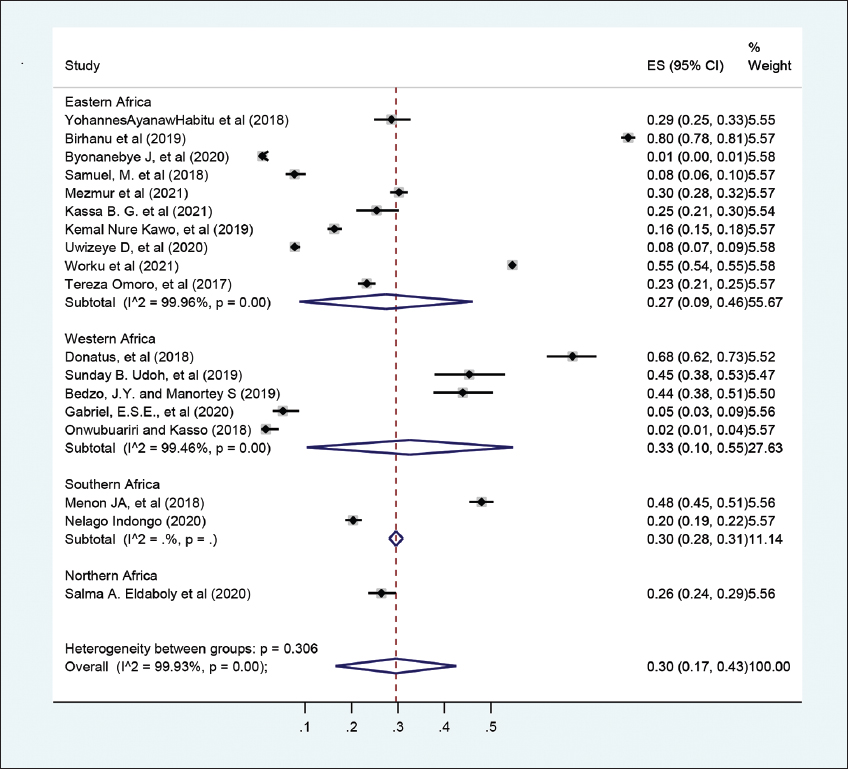

According to subgroup analysis by study region, West African countries had the highest prevalence of teenage pregnancy (33%, 95% CI: 10–55), while North African countries had the lowest prevalence of teenage pregnancy (26%, 95% CI: 24–29) [Figure 3].

- Subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa based on region, 2021

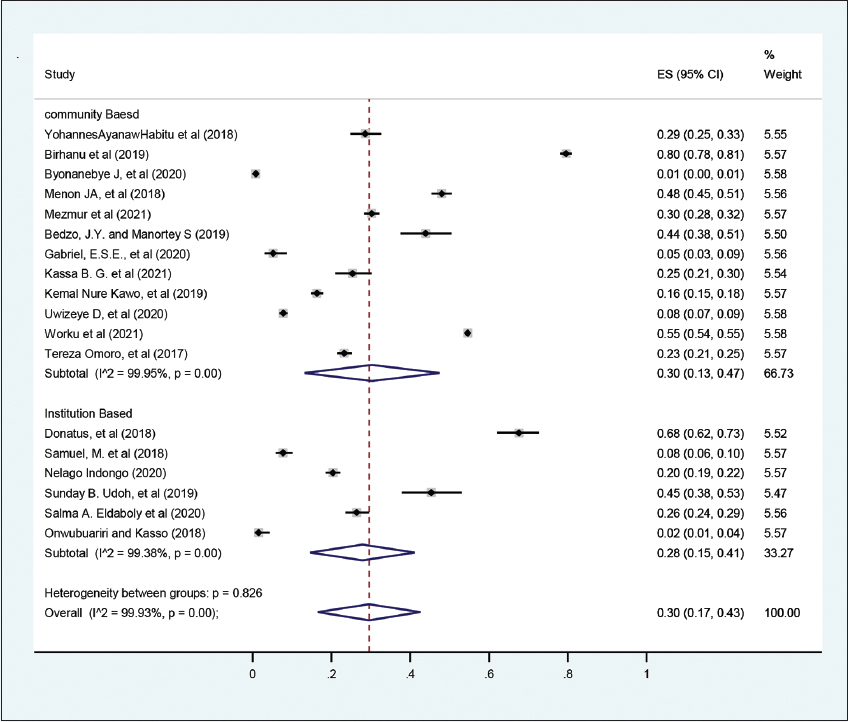

Based on subgroup analysis by setting in which studies are conducted, the highest prevalence (30%, 95% CI: 13–47) of teenage pregnancy was seen in studies conducted in community-based settings, while the prevalence of teenage pregnancy among institutional-based studies was 28% (95% CI: 15–41) [Figure 4].

- Subgroup analysis of the pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa based on region, 2021

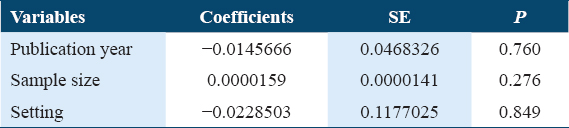

Meta-regression to check the heterogeneity

A meta-regression analysis was conducted since there was statistically significant heterogeneity, with I-square test statistics <0.05. The goal of the analysis was to identify the source of heterogeneity so that the findings could be correctly interpreted. The meta-regression analysis, however, found no significant variables that could explain the heterogeneity. There were no statistically significant study level covariates: Sample size, publication year, or study setting. As a result, the heterogeneity can be explained by factors other than those discussed in this review [Table 2]. It may be a result of compiling different studies that have been done with different methodology.

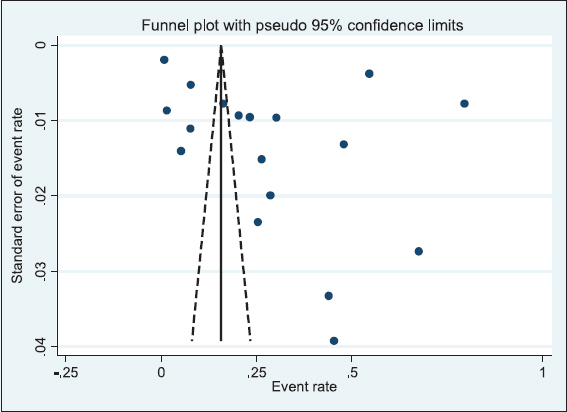

Publication bias

To observe publication bias, a visual inspection of the funnel plot was carried out [Figure 5]. It is asymmetric on the funnel plot. The prevalence rate among the various studies is different because the social realities are different and the study methodology also has been different, Egger’s test showed that there is no small study effect publication bias (P = 0.134).

- Funnel plot of prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

Predictors of teenage pregnancy in Africa

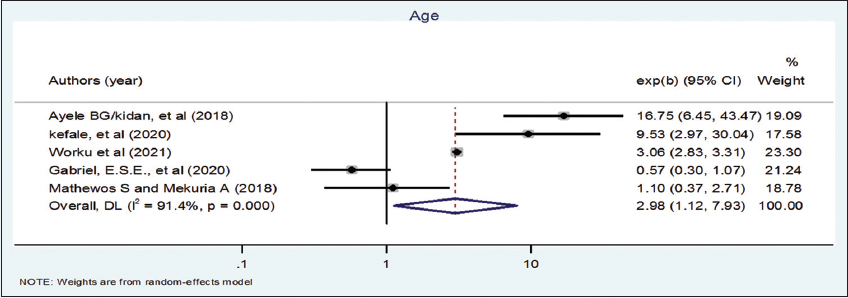

Age (below 15 versus 18–19)

A total of five studies were included to predict the association between age (18–19 years) and teenage pregnancy. Four studies included in this meta-analysis.[27,28,41,47] found a significant association between age and teenage pregnancy while the one article[32] found an insignificant association with teenage pregnancy. The pooled meta-analysis showed that there was a significant association between age (18–19 years) and teenage pregnancy. Teenagers whose age is 18–19 years were almost 3 times more likely to be pregnant than teenagers below the age of 15 (OR = 2.99, 95% CI = 1.124–7.927, P = 0.00001). The heterogeneity test indicated I2 = 91.4%, and the random model was employed for analysis [Figure 6].

- Association between age and teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

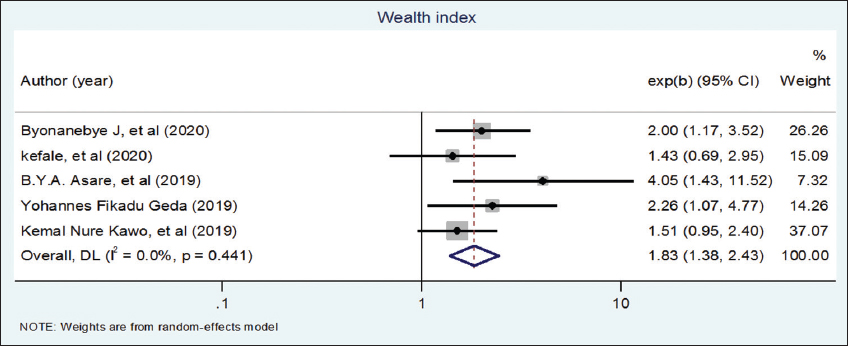

Wealth index (low vs. higher)

In this meta-analysis, five studies were included to see the association between wealth index and teenage pregnancy. Three articles included in this meta-analysis[24,43,49] were found significantly associated with teenage pregnancy, while two articles[26,27] found an insignificant association with teenage pregnancy. The pooled meta-analysis showed that there was a significant association between wealth index and teenage pregnancy. Teenagers who had a low wealth index were 1.84 times more likely to become pregnant than teenagers who had a higher wealth index (OR = 1.84, 95% CI = 1.384–2.433) [Figure 7].

- Association between wealth index and teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

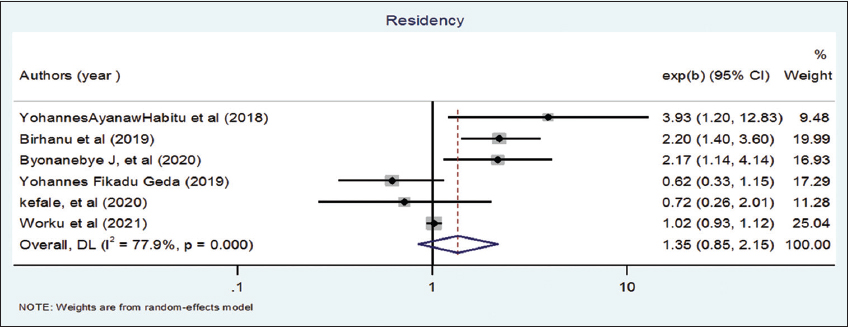

Place of residency (urban vs. rural)

In this meta-analysis, six studies were included to see the association between residency and teenage pregnancy. Three of the included articles[10,42,43] were found significantly associated with teenage pregnancy, while three of the articles[24,27,47] found an insignificant association with teenage pregnancy. The pooled meta-analysis showed that there was no significant association between residency and teenage pregnancy (OR = 1.35, 95% CI = 0.85–2.15). A random model was employed for analysis [Figure 8].

- Association between residency and teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

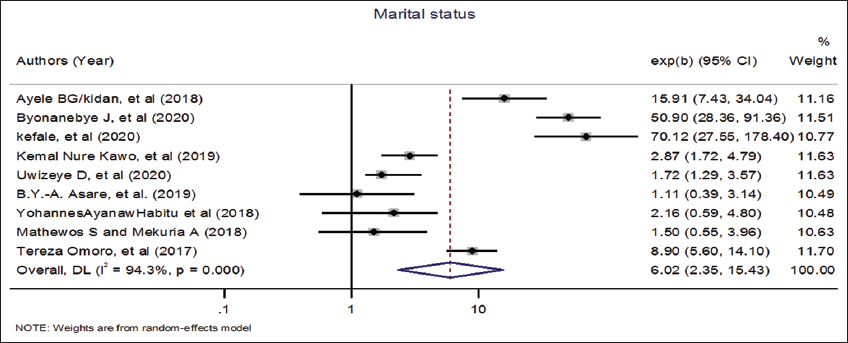

Marital status (married vs. not married)

In this meta-analysis, nine studies were included to see the association between marital status and teenage pregnancy. Six of the included articles[26,27,41,43,45,46] were found significantly associated with teenage pregnancy, while three articles[10,28,49] found an insignificant association with teenage pregnancy. The pooled meta-analysis showed that there was a significant association between marital status and teenage pregnancy. Teenagers who were married were 6 times more likely to become pregnant than teenagers who were not married (OR = 6.02, 95% CI = 2.348–15.43) [Figure 9].

- Association between marital status and teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

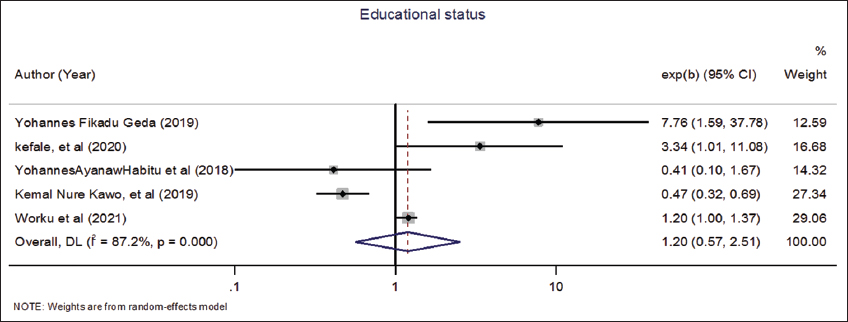

Educational status (primary educational status vs. no educational status)

A total of five studies were included to predict the association between educational status and teenage pregnancy. Four of the included studies[24,26,27,47] found a significant association between educational status and teenage pregnancy while the rest of one article[10] found an insignificant association with teenage pregnancy. The pooled meta-analysis showed that there was no significant association between educational status (primary educational status vs. no educational status) and teenage pregnancy (OR = 1.2 (95% CI = 0.57–2.51, P = 0.00001) [Figure 10].

- Association between educational status and teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

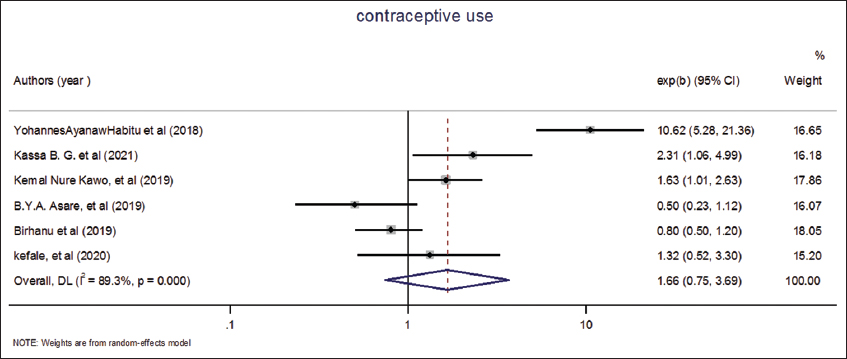

Contraceptive non-use

In this meta-analysis, six studies were included to see the association between contraceptive non-use and teenage pregnancy. Three of the included articles[10,26,44] were found significantly associated with teenage pregnancy, while three of the articles[27,42,49] found an insignificant association with teenage pregnancy. The pooled meta-analysis showed that there was no significant association between contraceptive non-use and teenage pregnancy (OR = 1.66 (95% CI = 0.747–3.69). A random model was employed for analysis [Figure 11].

- Association between contraceptive use and teenage pregnancy in Africa, 2021

Discussion

This comprehensive study provides valuable information on the prevalence and predictors of teenage pregnancy in Africa. In this review, a total of 23 studies done in different parts of Africa were included. Age, marital status, and wealth index were significantly associated with teenage pregnancy. Teenage pregnancy is a health issue because it poses maternal and perinatal risks. Maternal mortality is highest among teenagers as well as infant and child mortality rates were high among children born to teenage mothers.[52]

Evidence showed that low-income countries had the highest prevalence of teenage pregnancies.[2] Similarly, this study pointed out that the prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa was high (30% [95% CI: 17–43]). The pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Africa is higher than the pooled prevalence of teenage pregnancy in Latin America (6.5%), South (4.5%), and East Asia (0.7%).[53] The possible justification may associate with the unavailability of contraceptive services, poor attitude toward contraceptive, poor knowledge of teenage on their sexual health, and high prevalence of sexual assault and sexual violence in the low incoming country than in developed countries.[20,54,55] A similar study conducted in sub-Saharan African countries showed that the prevalence of teenage pregnancy was high.[56] Teenage pregnancy may be more prevalent due to a lack of access to contraceptive services, teenagers’ limited decision-making capacity, the community’s negative attitude toward contraceptive use, and peer pressure.[57-61] To alleviate the burden of teenage pregnancies, it is strongly recommended to involve prominent community leaders who play a key role in preventing early pregnancy in culturally acceptable ways. In addition, well-integrated sexuality-related education is linked to a contraceptive provision in the curriculum, as well as the formulation of laws and policies to improve access to contraceptive services.[52,62,63]

In this study, teenagers aged 18–19 were nearly 3 times more likely to become pregnant than teenagers under the age of 15. This could be because the majority of teenagers become sexually active when they reach the age of 18. This may also be related to the fact that child marriage at the age of 18 is common (28%) in developing regions, which predisposes teenagers to pregnancy.[3] This association between age and pregnancy has an implication for policymakers to work on setting strategies for preventing child marriage to reduce the burden of teenage pregnancy.

According to this study, a teenager who was married was 6 times more likely to become pregnant than teenagers who were not married. This finding was supported by evidence that showed that marriage was one of the predictors of teenage pregnancy.[52] This could be due to cultural pressure and peer pressure to have a child soon after marriage. Another reason could be that teenagers lacked knowledge and access to sexual and reproductive health services, including family planning, making them more likely to become pregnant.[64,65] The majority of 90% of all teenage births in Africa occur within marriage. In Africa, the proportion of teenage marriage was 54% and it is leveled as high compared to other worlds.[66] This results in the high prevalence of teenage pregnancy.[67,68] Furthermore, evidence showed that the median age for marriage in Africa was 15–19 which affects the children’s holistic live.[69] Evidence recommended that strengthening existing efforts on contraceptive usage among teenagers can avert teenage pregnancy.[64] It is advisable to encourage political leaders, planners, and community leaders to formulate and enforce laws and policies to prohibit the marriage of girls before 18 years of age.[52]

This study pointed out that teenagers who had a lower wealth index were 1.84 times more likely to become pregnant than teenagers who had a higher wealth index. This is in line with a systematic review and multilevel study done in sub-Saharan African countries which revealed that the wealth index is associated with teenage pregnancy and childbearing[70,71] The possible justification could be the improvement in the economic and cultural level makes the girl have more possibilities and life projects, decreasing the importance of traditional projects such as marriage and motherhood. Moreover, teenagers with higher wealth indexes are more likely to postpone marriage and early sexual activity. Evidence showed that teenagers who had a high wealth index had a lower desire to engage in sexual relationships with boys in exchange for cash and gifts, and a higher motivation to attend school.[72]

Strengths and limitations

The investigators used extensive and comprehensive search strategies from multiple databases. Published, unpublished studies, and gray literature were included in the study. Studies were evaluated for methodological quality using a standardized tool. The literature search was systematic and assessed all related studies within the desired scope. It appears that this is the first publication of a meta-analysis from across the African continent on the prevalence and risk factors involved with teenage pregnancy. It is possible that relevant publications, for example, publications reported in non-English language and local languages must have been missed. Studies with abstracts were the only ones included. This may affect the finding’s inclusiveness. The observed heterogeneity of the study is also the drawback of this meta-analysis.

Conclusion

Teenage pregnancy is still a major public health problem in Africa with a higher prevalence. Nearly a third of teenagers become pregnant in Africa. Age (18–19), wealth index, and marital status were the predictors of teenage pregnancy in Africa. Strengthening interventions that aimed to increase the economic independence of teenagers, decreasing child marriage, and contraceptive utilization among married teenagers can avert the problem of teenage pregnancy.

Authors’ Declaration Statements

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable due to the nature of the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the review findings of this study are available on submitting a reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Competing Interests

The authors declared that have no competing interests.

Funding

None.

Authors’ contributions

AE, TG, AS, and MS conceived and designed the review. AE*, TG, and AS carried out the draft of the manuscript, and AE* is the PI of the review. AE*, TG, and AS developed the search strings. AE, TG, MS, YB, AD, and AA screened and selected studies. AS, MS, AA, AD, YB, and AE extracted the data and evaluated the quality of the studies. AE, YB, AD, AA, and MS carried out analysis and interpretation. AE, TG, AS, MS, YB, AD, and AA rigorously reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the College of Health and Medical Sciences, Haramaya University, for the non-financial support.

References

- Empowerment of Adolescent Girls and Preventing Teenage Pregnancies and Population Management and Planning in Developing Nations. New York: UNICEF; 2016.

- Adolescent Pregnancy Evidence Brief-World Health Organization 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019.

- 2016. Adding it up:Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Adolescents. Available from: https://www.guttmacher.org/adding-it-up

- 2009. Teen Pregnancy Prevention. United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/winnablebattles/teenpregnancy/index.htm

- Pregnancy and early motherhood among adolescents in five East African countries:A multi-level analysis of risk and protective factors. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:59.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association between sexual violence and unintended pregnancy among adolescent girls and young women in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1370.

- [Google Scholar]

- Outcome of adolescent pregnancies in southwestern Nigeria:A case-control study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010;23:785-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A retrospective analysis of adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes in adolescent pregnancy:The case of luapula province, Zambia. Matern Health Neonatol Perinatol. 2018;4:20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Maternal morbidity and perinatal outcomes among women in rural versus urban areas. CMAJ.. 2016;188(17-18):E456-E465.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and factors associated with teenage pregnancy, Northeast Ethiopia, 2017:A cross-sectional study. J Pregnancy. 2018;2018:1714527.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy and its adverse obstetric and perinatal outcomes at Lemlem Karl hospital, Tigray, Ethiopia, 2018. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020:3124847.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent deliveries in urban Cameroon:A retrospective analysis of the prevalence, 6-year trend and adverse outcomes. BMC Res Notes. 2018;11:469.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and outcome of teenage pregnancy among attendants of labour room in Bassion general hospital-Egypt (cross section study) J Recent Adv Med. 2021;2:166-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hospital-based perinatal outcomes and complications in teenage pregnancy in India. J Health Popul Nutr. 2010;28:494-500.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent pregnancy:Risk factors, outcome and prevention. Chattagram Maa Shishu Hosp Med Coll J. 2016;15:53-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- An increased adverse fetal outcome has been observed among teen pregnant women in rural Eastern Ethiopia:A comparative cross-sectional study. Glob Pediatr Health. 2021;8:2333794x21999154.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progress Towards the SDGs:A Selection of Data from World Health Statistics 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

- Determinants of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa:A systematic review. Reprod Health. 2018;15:15.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence, predictors and adverse outcomes of adolescent pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa:A protocol of a systematic review. Syst Rev. 2017;6:247.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and determinants of adolescent pregnancy in Africa:A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Reprod Health. 2018;15:195.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of pregnancy among young people in sub-Saharan Africa:A systematic review and narrative synthesis. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4:e001499.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and metaanalyses:The PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses of individual participant data:The PRISMA-IPD statement. JAMA. 2015;313:1657-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia:A case-control study,. Curr Med Issues. 2019;17:112.

- [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of factors influencing teenage pregnancy in Namibia. Med Res Arch. 2020;8 Doi:10.18103/mra.v8i6.2102

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of teenage pregnancy in rural Ethiopia. J Health Med Nurs. 2019;68 Doi:10.7176/JHMN/68-02

- [Google Scholar]

- A multilevel analysis of factors associated with teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia. Int J Womens Health. 2020;12:785-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among school adolescents of Arba Minch Town, Southern Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2018;28:287-98.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors in Eastern Ethiopia:A community-based study. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:267-78.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of teenage pregnancy among girls aged 13-19 years in Uganda:A community based case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2019;19:211.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent Pregnancy. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2004.

- Prevalence and associated factors of teenage pregnancy among secondary and high school students in the Tiko health District, South West Region, Cameroon. J Biosci Med. 2020;8:99-113.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy:Prevalence, pattern and predisposing factors in a tertiary hospital, Southern Nigeria. Asian J Med Health. 2020;2020:1-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with adolescent school girl's pregnancy in Kumbo East health District North West region Cameroon. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;31:138.

- [Google Scholar]

- Wealth Index. In: Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research. Dordrecht: Springer; 2014.

- [Google Scholar]

- Making the Demographic and Health Surveys Wealth Index Comparable. Vol 9. Rockville, MD: ICF International Rockville; 2014.

- Predictors of wealth index in Malawi-analysis of Malawi demographic Health Survey 2004–2015/16. Public Health Pract (Oxf). 2021;2:100059.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect comparison between egger's test and begg's test in publication bias diagnosis in meta-analyses:Evidence from a pilot survey. Int J Res Stud Biosci. 2017;5:14-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- JBI's systematic reviews:Study selection and critical appraisal. Am J Nurs. 2014;114:47-52.

- [Google Scholar]

- Determinants of teenage pregnancy in Degua Tembien District, Tigray, Northern Ethiopia:A community-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0200898.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of teenage pregnancy in Ethiopia:A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Geographic variation and risk factors for teenage pregnancy in Uganda. Afr Health Sci. 2020;20:1898-907.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy and its associated factors among teenage females in Farta Woreda, Northwest, Ethiopia, 2020:A community-based cross-sectional study. Popul Med. 2021;3:1-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teen pregnancy in rural western Kenya:A public health issue. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2017;23:1-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of teenage pregnancy and the associated contextual correlates in Rwanda. Heliyon. 2020;6:e05037.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence and associated factors of adolescent pregnancy (15-19 years) in East Africa:A multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21:253.

- [Google Scholar]

- “Ring”your future, without changing diaper-can preventing teenage pregnancy address child marriage in Zambia? PLoS One. 2018;13:e0205523.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with adolescent pregnancy in the Sunyani municipality of Ghana. Int J Afr Nurs Sci. 2019;10:87-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy:Family and social characteristics and risk factors in Etinan, SubUrban Area of South-South Nigeria. SSRG Int J Med Sci. 2019;6:7-14.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors influencing teenage pregnancy in the lower Manya Krobo municipality in the Eastern region of Ghana:A cross-sectional study. Open Access Library J. 2019;6:1-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Guidelines on Preventing Early Pregnancy and Poor Reproductive Outcomes Among Adolescents in Developing Countries. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

- SDG Indicators:Global Database. New York: United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs; 2017.

- Contraceptive use in adolescents in Sub-Saharan Africa:Evidence from demographic and health surveys. Conn Med. 2014;78:261-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adding it up:Costs and Benefits of Meeting the Contraceptive Needs of Adolescents. New York: Guttmacher Institute; 2016.

- Prevalence of first adolescent pregnancy and its associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa:A multi-country analysis. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0246308.

- [Google Scholar]

- Girls cannot be trusted:Young men's perspectives on contraceptive decision making and sexual relationships in Bolgatanga, Ghana. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2018;23:139-46.

- [Google Scholar]

- Health care factors influencing teen mothers'use of contraceptives in Malawi. Ghana Med J. 2017;51:88-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Perceptions of young men at the free state school of nursing with regards to teenage pregnancy. Afr J Prim Health Care Fam Med. 2018;10:e1-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Attitudes towards contraception:focus groups with Arkansas teenagers and parents. Sex Educ. 2021;21:161-75.

- [Google Scholar]

- Support of adolescents to resist peer pressure and coercion to sexual activity. Int Nurs Rev. 2019;66:416-24.

- [Google Scholar]

- Teenage pregnancy and social disadvantage:Systematic review integrating controlled trials and qualitative studies. BMJ. 2009;339:b4254.

- [Google Scholar]

- WHO guidelines on preventing early pregnancy and poor reproductive outcomes among adolescents in developing countries. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52:517-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- Female adolescents'reproductive health decision-making capacity and contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa:What does the future hold? PLoS One. 2020;15:e0235601.

- [Google Scholar]

- Adolescent girls and young women:Policy-to-implementation gaps for addressing sexual and reproductive health needs in South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2020;110:855-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Has child marriage declined in sub-Saharan Africa?An analysis of trends in 31 countries. Popul Dev Rev. 2017;43:7-29.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inequalities in early marriage, childbearing and sexual debut among adolescents in sub-Saharan Africa. Reprod Health. 2021;18:117.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India:A cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet. 2009;373:1883-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Age at marriage and modernisation in sub-Saharan Africa. Southern African J Demogr. 2004;9:59-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Multilevel determinants of teenage childbearing in sub-Saharan Africa in the context of HIV/AIDS. Health Place. 2017;46:37-48.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with teen pregnancy in sub-Saharan Africa:A multi-country cross-sectional study. Afr J Reprod Health. 2016;20:94-107.

- [Google Scholar]

- Economic support, education and sexual decision making among female adolescents in Zambia:A qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:1360.

- [Google Scholar]