Translate this page into:

Prognostic significance of the tumor budding and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients

Address for correspondence: Ola M. Omran, Department of Pathology, College of Medicine, Qassim University, Buridah, Qassim Region, Saudi Arabia/Department of Pathology, Faculty of Medicine, Assiut University, Assiut, Egypt. E-mail: ola67oh@yahoo.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Qassim Uninversity and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

ABSTRACT

Objective:

In spite of great advance in the management of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), the prognostic factors are still obviously not understood. The role of tumor budding (TB) and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in HCC as pathological parameters affecting prognosis stands principally unknown.

Methods:

Seventy-four surgical resection pathology specimens of HCC patients were used. Assessment of TB and TILs were performed using hematoxylin-eosin-stained slides. Follow-up data were collected over a 5-year period to determine disease-free survival rates, overall survival (OS) rates, and how they related to TB, TILs, and other clinicopathological factors.

Results:

There was a significant statistical association between high-grade TB and lymphovascular embolization (LVE), tumor necrosis, and grade of HCC with P = 0.003, 0.036, and 0.017, respectively. The positive TILs group showed a statistically significant correlation with histological grade, LVE, and serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) level with P = 0.002, 0.006, and 0.043, respectively. Multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model revealed that TILs are not an independent pathological factor for disease-free and OS, although TB is an independent pathological factor for both.

Conclusions:

In all HCC patients, TB was seen, and there was a significant link between the grade of the HCC and the presence of tumor necrosis, LVE, and high-grade TB. The majority (92%) of HCC patients had TILs, and there was a strong relationship between the histological grade, LVE, and serum AFP level. While TILs show variation of the immunologic reaction to the tumor, TB tends to suggest a hostile biologic nature and a bad prognosis.

Keywords

Hepatocellular carcinoma

overall survival

tumor budding

tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes

Introduction

Primary liver cancer constitutes the fifth most frequent cancer in men and the seventh in women.[1] Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) constituting 90% of all primary liver malignancies, represents the fifth common cancer in people.[2-5] The peak incidence for HCC is approximately 70 years of age and barely occurs before the age of 40 years. HCC, which has a rapidly increasing incidence in the past 20 years, constitutes a major global health issue.[6-8]

Chronic liver diseases, which comprise alcohol intake, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and also chronic viral hepatitis ending with cirrhosis, are considered the most common etiologies causing HCC.[9-11]

The overall survival (OS) of Egyptian HCC patients exceeds sub-Saharan and East African countries.[9]

Hospital-based studies have demonstrated a rising incidence of HCC. This could be attributed to rapid progress in screening programs and diagnostic tools[8] and an increase in the incidence and complications of infection with chronic viral hepatitis[12] which is the major significant risk factor in developing HCC in Egypt, particularly in rural areas due to low socioeconomic status.[13]

In spite of the improvement in the screening programs, only 40% of HCCs are diagnosed in the curative stage, however, nearly 55% of patients are diagnosed at either transitional or an advanced stage.[10] The prognosis of advanced stages of HCC is poor as a result of considerable tumor burden, increased frequency of liver cell failure, and decline in health status limiting patients’ treatment.[14-17]

Although surgical and medical therapy of HCC have been significantly improved, the prognosis of HCC remains bad. The overall 5-year survival rate of resected HCC patients is just 30%.[17] Inadequate systemic therapy is one reason accredited to the unfavorable prognosis in HCC.[18,19]

The median OS time of HCC patients in the advanced stages was prolonged from eight to eleven months by a drug known as Sorafenib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor).[20] Later on, atezolizumab combined with bevacizumab in 2020 became the first regimen to show superior OS to sorafenib, gaining FDA approval for unresectable or metastatic cases.[21]

Prognostic groups are often distinguished using TNM staging. With TNM staging, the patients have been divided into various prognostic groups by several histopathologic subtypes based on WHO categorization. However, histologic types, such as cancer grade continue to have a poor predictive value.[22]

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) are known as a group of lymphocytes that circle malignant cells and perform different functions in various subsets. They are utilized in the evaluation of prognosis and determination of treatment of various types of cancer with different success degrees.[23]

TILs are a diverse group that, most significantly, includes T lymphocytes, macrophages, myeloid-derived suppressor cells, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells.[24]

Certain researches evaluated the prognostic value of TILs in many types of cancers, such as carcinomas of the stomach, breast, ovary, and lung. In addition, TILs significantly correlated with patients’ outcomes in various carcinomas along with HCC. Other studies demonstrated the importance of TILs as a primary tumor and metastasis treatment in the form of immunologic therapy.[25]

The immune system displays an energetic defensive function against malignant tumors through the recognition and elimination of malignant cells. Various tumor-associated antigens are expressed by cancer cells inducing an immunological response against cancer. Nevertheless, the immune system occasionally has difficulty to distinguish the specific target or produces an inadequate response that fails in cancer destruction. Moreover, cancer cells sometimes hide from the immune system through the production of a sequence of immune escape mechanisms which is responsible for the immune system’s inability to terminate or control cancer.[26,27] Hence, immunotherapy could be considered as a hopeful approach to anticancer treatment.[28]

Although tumor budding (TB), a distinctive clinical characteristic, is linked to an aggressive course in a number of malignant tumors, its prognostic significance in HCC is unclear as of yet. It has been proven to be a valued prognostic limitation in the pathological staging of colorectal cancer.[23]

The process by which a single or a collection of malignant cells separate from the main tumor at the invasive front and infiltrate the connective tissue in the vicinity is referred to as TB. It’s connected to the epithelial-mesenchymal transition where the malignant epithelial cells gain stromal cell characteristics that allow their infiltration into the surrounding connective tissue, and penetration of the vascular spaces, thus reaching distant sites where they sediment, forming distant metastasis.[29]

In numerous solid cancer types, lymph vascular invasion, lymph node and distant metastases, and worse patient survival are all associated with the TB process, which has been identified as a characteristic of an adverse tumor outcome.[30]

Therefore, this study proposes to detect the association between TB and TILs with other clinicopathological variables. Furthermore, we aim to evaluate the prognostic relationship between TB and TILs and OS rates.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study was performed on seventy-four surgical resection pathology specimens of HCC patients identified from the surgical pathology department at South Egypt Cancer Institute (SECI), Assiut University from January 2011 to December 2017. Histological analysis was used to validate each patient’s diagnosis. Following surgical removal of the tumor, clinical information was gathered from the pathology and oncology department registry at SECI. From the pathology archives, diagnostic hematoxylin and eosin (HE)-stained histology samples were taken. The staging was done using the TNM classification, 8th edition. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from SECI where the study was performed (Approval number: 7885).

Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria

Our study was performed according to the following inclusion criteria: (1) histopathological diagnosis of primary HCC; (2) patient age more than 18 years old; (3) patient performance status (0–2); (4) patient has undergone radical resection of the tumor. The following exclusion criteria were used: (1) The patient has not undergone TACE or received target therapy; (2) the patient has received adjuvant therapy.

Clinical and histopathological assessment

Cases were assessed for TB, TILs, and for other clinicopathological variables.

Assessment of TB and TILs using HE-stained slides cut at 5u for formalin fixed paraffin embedded cases by experienced pathologists.

To determine whether tumors’ most invasive regions were present or not, slides were initially inspected at low power magnification. After that, they were inspected at a high magnification (×200), and in five adjacent microscopic areas, the tumor bud number—solitary or clusters of up to five malignant cells —was tallied. Histological Grading for TB included grades 1 (0–4), 2 (5–9), and 3 (10). In addition, instances classified as high-grade TB had ten or more buds, whereas those ranked as low-grade TB had zero to nine buds.[22]

Using the criteria outlined by Hendry et al. and Salgado et al., the proportion of TILs in a single full-face, HE-stained tumor slice underwent histopathological investigation.[27,31] The quantity of TILs in the connective tissue around the labeled malignant cells was counted quantitatively in every field while magnified by 400 times. TILs were described as lymphocytes that infiltrate tumor stroma and reflected as a percentage in the area under investigation. Areas where artifacts were crushed were excluded. If there was more than 50%, more than 10%, <10%, or none of the stroma around the invasive tumor cell nests had lymphoplasmacytic infiltration, then the proportional scores were 3, 2, 1, and 0. For TILs, a score of 2 was seen as favorable, while values of 1 and 0 were regarded as unfavorable.

Follow-up data were performed for 5 years for each case to ascertain disease-free survival and OS with their correlation with TB, TILs, and other clinicopathological parameters.

Statistical analysis

Analytical studies were carried out utilizing SPSS statistical software package version 24 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL). The chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test evaluated the association between categorical variables. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients were applied to estimate bivariate correlations between research variables. A probability value of <0.05 was regarded as significant statistically.

Results

Seventy-four cases of various histopathological HCC grades were enrolled in the current study. Clinical information and pathological specimens have been attained from department archives of the Medical Oncology and the Pathology in SECI.

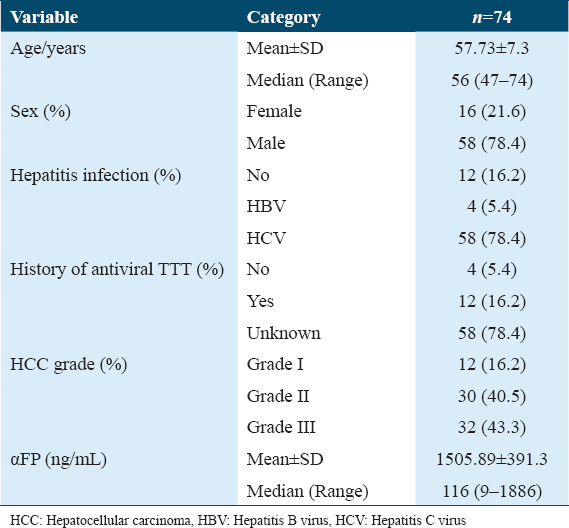

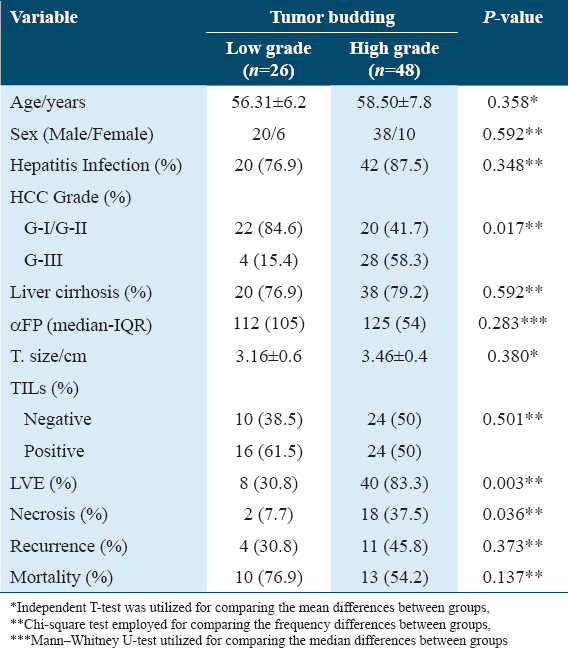

Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the studied cases

Demographic and clinicopathologic characteristics of the HCC patients are reported in Table 1. Data disclosed that the ages of the patients ranging from 47 to 74 years, with a mean of 57.73 ± 7.3 years. Furthermore, men comprised nearly 58/74 cases (78.4%) and females were about 16/74 cases (21.6%). From the total number of patients with HCC, 58 (78.4%) patients were hepatitis C virus (HCV) positive and 4 patients (5.4%) were HBV positive but as little as 12 patients of the total number of patients (16.2%) have an antiviral treatment history. Based on WHO classification, histopathologic examination disclosed that 32 (43.3%) cases were Edmondson grade III, 30 (40.5%) cases were Edmondson grade II and 12 (16.2%) cases were Edmondson grade I. Regarding the presence of associated cirrhosis, fifty-eight (78.4%) of cases had liver cirrhosis. Surgical resections were carried out in all HCC cases. HCC patients had increased levels of αFP with Mean ± SD were 1505.89 ± 391.3.

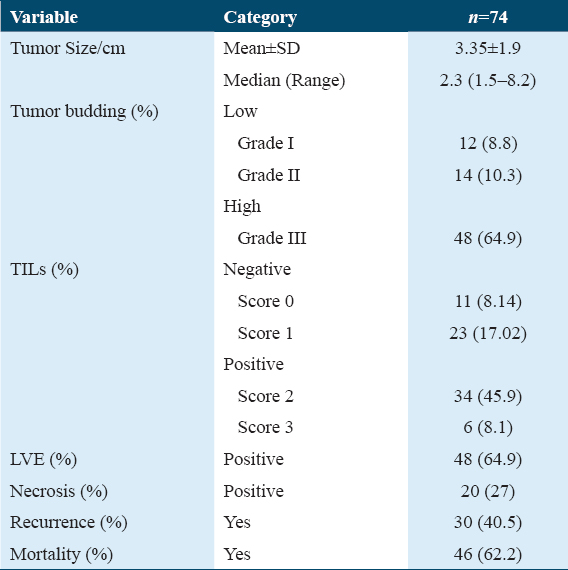

Tumor-associated factors and histopathologic results

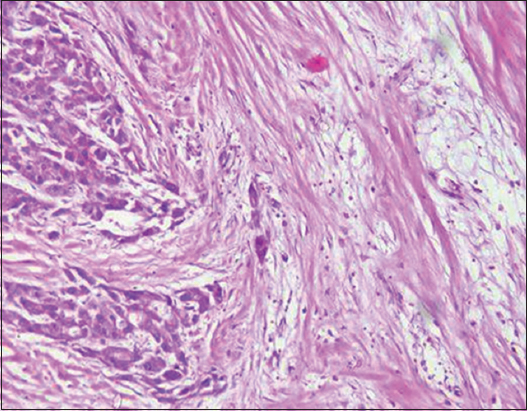

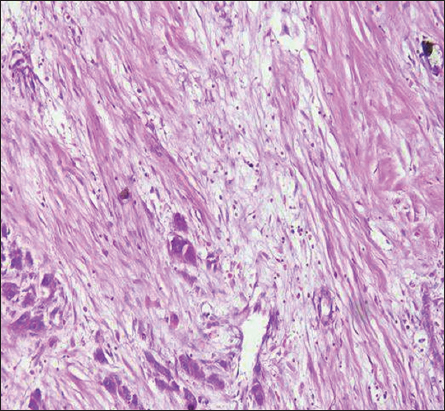

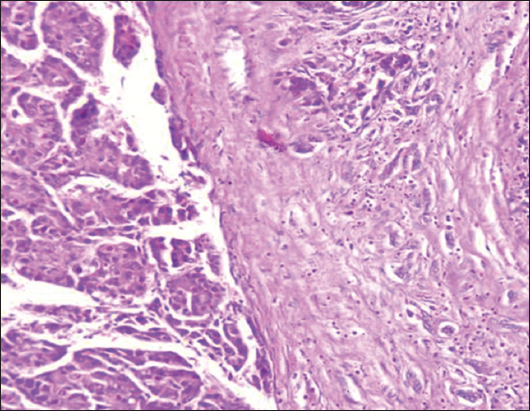

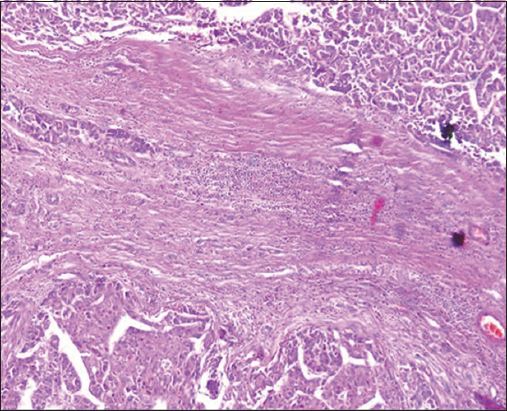

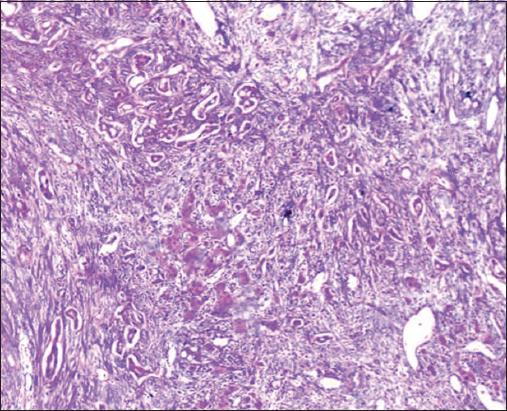

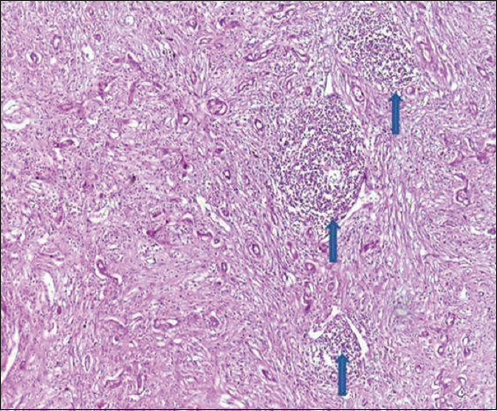

Tumor-associated factors in the studied Cohort were disclosed in Table 2. The sizes of the tumors varied from 1.5 to 8.2 cm with a mean of 3.35 ± 1.9. Tumor size smaller than 5 cm was found in 60/74 cases (81%), and more than 5 cm in 14/74 cases (19%). The current study involved different HCC histological grades. High TB was detected in 48/74 (64.9%) cases while 26/74 (35.1%) cases showed low TB [Figures 1-3]. TILs were detected in 91.86% of HCC cases; 34 (45.9%) cases demonstrated negative scores of TILs and 40 (54.1%) cases showed positive scores of TILs. Lymphovascular embolization (LVE) was positive in 48/74 cases (64.9%) and tumor necrosis was detected in 20/74 (27%) cases.

- H&E stain ×200 power magnification, grade I tumor budding (Low-grade tumor budding) in hepatocellular carcinoma

- H&E stain, ×200 power of magnification demonstrating grade III tumor budding (high-grade tumor budding) in hepatocellular carcinoma

- H&E stain ×200 power magnification, grade II tumor budding (low-grade tumor budding) in hepatocellular carcinoma

A total of 30/74 patients (40.5%) had tumor recurrence. In this study, 28 cases (37.8%) were still alive with a mean survival time of 32.78 months, and 46/74 cases (62.2%) were dead with a mean survival time of 14.88 months.

Clinicopathological features such as age, sex of the patients, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels, hepatitis infection, associated liver cirrhosis, tumor size, recurrence, mortality, and TILs demonstrated no statistically significant differences between low and high-grade TB groups. Expectedly, high-grade TB was remarkably associated with LVE, tumor necrosis, and grade of HCC with P = 0.003, 0.036, and 0.017, respectively. Table 3 shows the relationship between TB and clinicopathological factors.

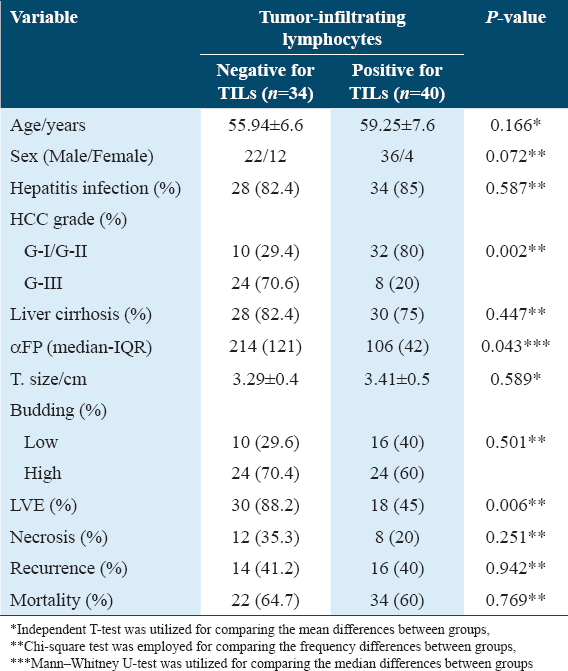

We also detected no statistically significant association between the score of TILs and age, sex, tumor necrosis, tumor stage, background liver cirrhosis, TB, hepatitis, recurrence, and tumor mortality. However, the positive TILs group showed statistically significant association with histological grade, LVE, and serum AFP level with P = 0.002, 0.006, and 0.034, respectively.

Figures 4-7 show the representative HE images of different TILs scores. Table 4 shows the relationship between TILs and clinicopathologic variables.

- H&E stain, ×400 power of magnification demonstrating score 0 of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (Negative TILs) in hepatocellular carcinoma

- H&E stain, ×400 power of magnification demonstrating score 1 of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (Negative TILs) in hepatocellular carcinoma

- H&E stain, ×400 power of magnification demonstrating score 2 of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (positive TILs) in hepatocellular carcinoma

- H&E stain, ×400 power of magnification demonstrating score 3 of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) (positive TILs) in hepatocellular carcinoma, blue arrow showed lymphoid aggregates

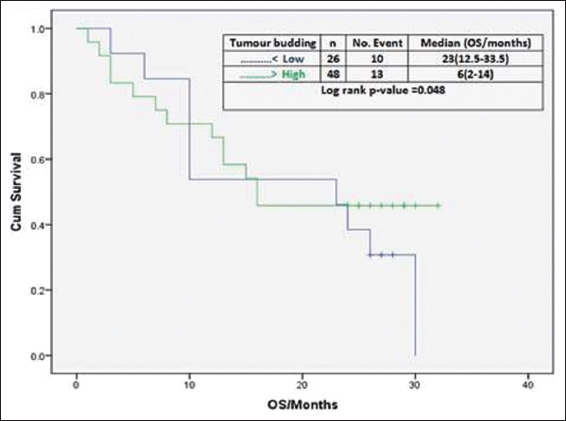

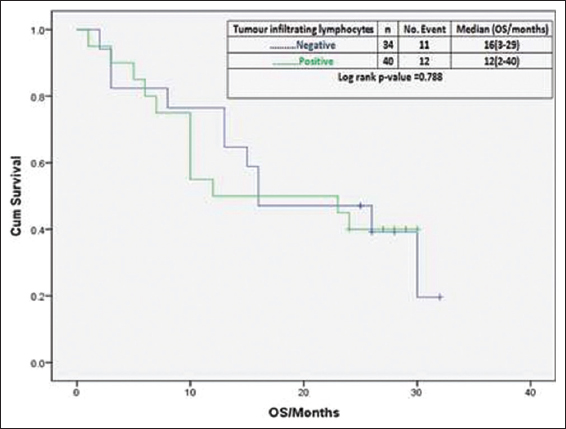

Multivariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazard model was performed and showed that TB is an independent pathological factor for overall and disease-free survival and surprisingly TILs are not an independent factor for OS as illustrated in Figures 8 and 9.

- Effect of tumor budding on overall survival

- Effect of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes on overall survival

Discussion

Many researches were concerned with the identification of predictive and prognostic factors in HCC patients. HCC risk factors evaluation and the improvement of the treatment strategy, need more understanding of clinicopathological conditions and the prognostic factors that affect tumor differentiation, proliferation, and distant metastasis.[29] Our study’s purposes were to detect the association between TB and TILs with clinicopathological variables and to evaluate the prognostic relationship between TB and TILs with OS rates. We carried out this preliminary investigation to test our hypothesis and to fulfill the existing gap in the literature.[32]

In this study, we demonstrated that HCC patients presented at the mean age of 57.73 ± 7.3 years. This finding is in accord with research performed by Le et al.[33] demonstrating that the majority of HCC patients were diagnosed at age fifty years and older. Research done by Yang et al.[34] found that patients with HCC had an age ranging from 40 to 60 years old. However, HCC occurs one decade older at the Asia-Pacific region but generally speaking, HCC is seldom seen before 40 years old.[35]

On the contrary to the findings of a previous study that patient age at HCC diagnosis in Arabic nations is younger by one decade than the Western Japanese and Chinese nations, the data of this study showed that the majority of HCC patients were aged ≥50.[36]

This finding might be interpreted through dissimilar population pyramids in evolving nations, dietary and physical influences that enhance neoplastic transformation and the higher incidence of positivity of HCV (78.4%) in HCC patients enrolled in our research.[36]

With regard to sex, the findings of this study showed that HCC demonstrated men domination with men-to-women ratio of 3.6:1, which is in accordance to other studies like Liu et al. that also detected men predominance with men-to-women ratio of 3.55:1, respectively.[37] This finding of male predominance may be linked to the protective function of estrogen in women and might be related to differences in HCV infection incidence which has been recognized as a crucial predisposing factor for HCC, the age of the patients at the time of viral infection as well as the existence of another risky factor.[38] Thus, sex differences in HCC incidence could be correlated with biological factors as well as behavioral risk factors.

In Egypt, HCC is one of the crucial public health issues and Egypt has a substantial HCV burden.[19] The correlation between HCV and HCC is a major and principal area for investigation. Our findings showed that 78.4% of HCC patients were infected with HCV and 16% of patients have antiviral treatment history with 84% of patients had not received any medical treatment they do not know. Furthermore, our study revealed that 78.4% of HCC patients had cirrhosis of the liver. A previous study demonstrated that liver cirrhosis is usually found in 80–90% of HCC cases representing the most crucial risk factor for HCC.[35] The high percentages of HCV in HCC patients in this study might be elucidated by the persistence of chronic inflammation as a result of HCV infection as well as the absence of antiviral treatment in 84% of patients representing a key mechanism for the cirrhotic occurrence succeeded by development of HCC.[39]

Our work showed that moderately and poorly differentiated HCC was the predominant form of differentiation (84% of cases). This finding is in agreement with Zheng et al. and Khoury et al. who reported that 60% and 86% of their cases were moderately and poorly differentiated HCC.[40,41] These findings were in contrast to a study done by Kaseb et al. who investigated 67 cases, out of which 33(50%) cases were well-differentiated. This controversy might be explained by the genotypic differences between other groups and our population samples.[42]

In our present investigation, 19% of HCC patients presented with a tumor size 5 cm or larger (≥5 cm) and 81% of tumor size were smaller than 5 cm (<5 cm). A recent study showed 47% of HCC patients had a tumor size ≥5 cm and, 53.3% of HCC patients showed tumor sizes <5 cm.[43]

Wu et al. investigated 57,920 HCC cases, and 46% were having size ≥5 cm. Li et al. detected that more than 60% of chosen HCC patients had a size ≥5 cm and validated that tumor size at diagnosis could be used as an independent-risk predictor associated with histological grade, selection of surgery, and survival in HCC.[44,45]

The large tumor size detected in the current study might be explained by the late patients’ presentation, usually coming from rural regions suffering from low income and poor education, as well as reduced in efficiency of screening programs for early detection of HCC in the community.

Impressively, in the current investigation, the prevalence of TB in HCC was detected in 64.9% of cases that exhibited high/positive TB and 35.1% of cases exhibited low/negative TB. This finding is in accordance with research performed by Kairaluoma et al. who detected that 40% of HCC cases had high/positive TB.[46] TB is among the top most significant prognostic markers in HCC that indicates aggressive biologic activity and a bad prognosis. An explanation for the tumor’s budding might be the morphologic shift to a fibroblast-like look, which occurs concurrently with the epithelial-mesenchymal transition phase.[46]

In this study, TB and TILs are considered two promising candidate prognostic indicators of HCC. While TILs show the variety of immune response to the tumor, TB seems to specify a combative nature of malignancies. The results of the current investigation show associations between TB and TILs with patients’ prognostic outcomes and clinicopathological characteristics.

As high-grade tumor blossoming is related with short-term patient survival, TB has an unfavorable influential factor in HCC, regardless of grade and the clinical criteria. In addition, the presence of LVE, the discovery of tumor necrosis, and high-grade HCC were all substantially correlated with TB.

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition, which occurs when epithelial cells gain mesenchymal, invasive, and tumorigenic features, might account for the increased TB seen in this research.[46]

The evolution of anti-cancer immunological response is considered to be connected with tumor neoantigen numbers that stand for mutated peptides.[2] According to this inclusive hypothesis, we detected those patients having positive TILs were significantly associated with lower incidence of LVE, lower tumor grade, and lower level of AFP. Furthermore, as expected tumors with negative TILs were associated with higher levels of serum AFP, higher tumor grade, and higher incidence of LVE. However, at the same time, TILs are not considered an independent factor affecting the survival of patients with HCC.

TILs were detected in 91.86% of HCC cases. Previous studies demonstrated that TILs represent host-immune responses to tumors through the interaction between tumor cells and the immune system and also clarified that activated TILs can mediate an antitumor immune response that ultimately leads to cancer cells death.[47,48] Furthermore, the presence of TILs leads to the creation of central memory T and B cells which disseminate and restrict cancer progression.[49] Previous studies discovered that TILs involve a variety of lymphocyte subgroups, which include innate and adaptive immune cells, in particular macrophages, T lymphocytes, mast cells, and NK cells. They concluded that TILs play crucial roles in the development, progression, prognosis, and immunotherapeutic-management of HCC.[50,51] The presence of TILs in all our HCC cases could be explained by the easy access of the immune cells to the tumor through the blood vessels and tumor stroma due to the high vascularity of the liver.[51]

LVE was positive in 64.9% of patients. Antecedent research described LVE by the presence of malignant cells inside a space encircled by red blood cells or lymphocytes and adherent to the vessel wall.[52] In agreement with this study, Hsieh et al. reported the presence of LVE in 39/89 (43.8%) of HCC patients.[53] Similar results were obtained by Song et al. who showed that LVE was present in 55% of breast carcinoma patients and was associated with age ≤40 years, high histological grade, tumor size ≥2 cm, and the involved lymph node numbers.[54] These studies validated LVE as a significant indicator of poor prognosis in cancer patients and also considered one of the most important risk factors for predicting lymph node metastasis.[54,55]

Tumor necrosis was found in 27% of our HCC cases. Prior research executed on 919 cases from all over the world revealed that necrosis in HCC is correlated to survival (overall and recurrence-free) and is commonly detected in malignancy with bad general characteristics. Moreover, they reported that >50% necrosis was able to upstage small favorable cancers (T1 HCC with >50% necrosis had survival equivalent to a T2 tumor, and T2 tumors with >50% necrosis became equivalent to T3 tumors in terms of survival).[56]

Previous research reported that tumor necrosis was present in 157/335 (46.9%) of HCC cases and its detection was significantly correlated with vascular invasion, tumor size, poor cancer-specific OS, and recurrence-free survival (RFS).[54] Moreover, Ling et al. observed that tumor necrosis might be regarded as a parameter indicating cancer-aggressiveness in HCC.[57] The inability to find any predictive power of tumor necrosis might be explained by the limited number of cases recorded in the current study.

Our observation showed that about 40.5% of HCC patients suffered from tumor recurrence after tumor surgical resection. In concordance with our findings, preceding research reported that the recurrence rate between 5 and 10 years after surgical resection of HCC patients was 27%.[58] The annual HCC recurrence rate following surgical resection is nearly ≥10%, which reaches to 80% after 5 years.[59]

There were some limitations in this study. First, the studied number of patients was limited. Second, more specification for the nature of TILs is needed both at a genetic and immunohistochemical level. However, relationships between TB and TILs with other prognostic and clinicopathological variables were demonstrated in our study.

Conclusions

Our observation showed that TB was detected in all HCC cases with significant statistical association between high-grade TB and LVE, tumor necrosis, and HCC grade. TILs were detected in most (92%) of HCC cases with significant correlation with histological grade, LVE embolization, and serum AFP level. TB reveals to denote an aggressive biological behavior and poor prognosis, while TILs reflect the variation in immunological reaction to tumors. In this study, TB and TILs are considered two promising nominee prognostic indicators of HCC.

Future Directions

Our preliminary findings demand deeper studies, such as performance on a larger number of HCCs of different grades to enhance the statistical sensitivity and power with reducing the statistical bias and investigation of genetic and Immunohistochemical factors that increase the depth of understanding of TB and TILs.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

All the informed consents for publication from the patients were obtained. Institutional Review Board approval was obtained from SECI where the study was performed (Approval number: 7885).

Availability of Data and Material

All data generated or analyzed in this study are included in this published article. The data are available on request.

Competing Interests

None.

Funding Statement

None.

Author Contributions

Ahmed Mahran Shafiq: Principal investigator, data collection & tabulation, writing – reviewing and editing. Noura Ali Taha: Data collection, analysis of results, writing – review and editing. Amen Hamdy Zaky: Writing –reviewing, and editing of original draft. Abdallah Hedia Mohammed: Data analysis, writing –reviewing, and editing. Ola M. Omran: Pathology part writing and tabulation, data extraction and tabulation. Lobaina Abozaid: Pathology part, data analysis and extraction. Hagir H. T. Ahmed: Pathology part, data extraction and tabulation. Mahmoud Gamal Ameen: Pathology part writing and tabulation, reviewing, and editing.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- Global cancer statistics 2018:GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394-424.

- [Google Scholar]

- An update of biochemical markers of hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2016;10:121-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- FOS-like antigen 1 expression was associated with survival of hepatocellular carcinoma patients. World J Oncol. 2023;14:285-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessment of the proliferative marker Ki-67 and p53 protein expression in HBV- and HCV-related hepatocellular carcinoma cases in Egypt. Int J Health Sci (Qassim). 2008;2:27-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- EASL clinical practice guidelines:Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2018;69:182-236.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatocellular carcinoma:ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2018;29:238-55.

- [Google Scholar]

- A global view of hepatocellular carcinoma:Trends, risk, prevention and management. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;16:589-604.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis, staging, and management of hepatocellular carcinoma:2018 Practice guidance by the American association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2018;68:723-50.

- [Google Scholar]

- Viral hepatitis and liver cancer. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2017;372:20160274.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of liver cancer in Nile delta over a decade:A single-center study. South Asian J Cancer. 2018;7:24-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cancer incidence in Egypt:Results of the national population-based cancer registry program. J Cancer Epidemiol. 2014;2014:437971.

- [Google Scholar]

- Epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma:Target population for surveillance and diagnosis. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2018;43:13-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- Role of TGF-b1 and C-Kit mutations in the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in hepatitis C virus-infected patients:In vitro study. Biochemistry (Mosc). 2019;84:941-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of toll-like receptors 2(TLR2) and TLR 4 gene variations on HCV susceptibility, response to treatment and development of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic HCV patients. Immunol Invest. 2020;49:462-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Actin-like 6A predicts poor prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma and promotes metastasis and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Hepatology. 2016;63:1256-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatitis C infection in Egypt:Prevalence, impact and management strategies. Hepat Med. 2017;9:17-25.

- [Google Scholar]

- The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in Egypt 2015:Implications for future policy on prevention and treatment. Liver Int. 2017;37:45-53.

- [Google Scholar]

- Corrigendum to 'Ramucirumab as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib:Patient-focused outcome results from the randomised phase III REACH study'[Eur J Canc 81 (2017) 17-25. Eur J Cancer. 2018;100:135-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatobiliary cancers, version 2.2021, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2021;19:541-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- A classification based on tumor budding and immune score for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2020;9:1672495.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumour budding correlates with aggressiveness of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2016;36:4781-5.

- [Google Scholar]

- Identification of critically carcinogenesis-related genes in basal cell carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther. 2018;11:6957-67.

- [Google Scholar]

- Basal cell carcinoma:Epidemiology;Pathophysiology;Clinical and histological subtypes;And disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-17.

- [Google Scholar]

- Canvassing prospects of glyco-nanovaccines for developing cross-presentation mediated anti-tumor immunotherapy. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:2049.

- [Google Scholar]

- Assessing tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in solid tumors:A practical review for pathologists and proposal for a standardized method from the International immunooncology biomarkers working group:Part 1:Assessing the host immune response, TILs in invasive breast carcinoma and ductal carcinoma in situ, metastatic tumor deposits and areas for further research. Adv Anat Pathol. 2017;24:235-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Taking tumour budding to the next frontier - A post International Tumour Budding Consensus Conference (ITBCC) 2016 review. Histopathology. 2021;78:476-84.

- [Google Scholar]

- The evaluation of Tumor-Infiltrating Lymphocytes (TILs) in breast cancer:Recommendations by an International TILs Working Group 2014. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:259-71.

- [Google Scholar]

- Matrix metalloproteinase 2 overexpression and prognosis in colorectal cancer:A meta-analysis. Mol Biol Rep. 2013;40:617-23.

- [Google Scholar]

- Ages of hepatocellular carcinoma occurrence and life expectancy are associated with a UGT2B28 genomic variation. BMC Cancer. 2019;19:1190.

- [Google Scholar]

- Impact of country of birth on age at the time of diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in the United States. Cancer. 2017;123:81-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Global patterns of cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2010;19:1893-907.

- [Google Scholar]

- Hepatocellular carcinoma in the world and the Middle East. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2010;2:31-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Gadoxetic acid disodium-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging outperformed multidetector computed tomography in diagnosing small hepatocellular carcinoma:A meta-analysis. Liver Transpl. 2017;23:1505-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Real impact of liver cirrhosis on the development of hepatocellular carcinoma in various liver diseases-meta-analytic assessment. Cancer Med. 2019;8:1054-65.

- [Google Scholar]

- High expression of Rap2A is associated with poor prognosis of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2017;10:9607-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Expression of Intestinal Trefoil Factor (TFF-3) in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Gastrointest Cancer. 2005;35:171-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating clinical and prognostic implications of Glypican-3 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:69916-26.

- [Google Scholar]

- CDC6 is a possible biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2021;14:811-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Importance of tumor size at diagnosis as a prognostic factor for hepatocellular carcinoma survival:A population-based study. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4401-10.

- [Google Scholar]

- FOS-like antigen 1 is a prognostic biomarker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Saudi J Gastroenterol. 2019;25:369-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumour budding and tumour-stroma ratio in hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:38-45.

- [Google Scholar]

- Inflammation and cancer:Advances and new agents. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015;12:584-96.

- [Google Scholar]

- Comprehensive analysis of the clinical significance, immune infiltration, and biological role of MARCH ligases in HCC. Front Immunol. 2022;13:997265.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in hepatocellular carcinoma using hematoxylin and eosin-stained tumor sections. World J Clin Cases. 2022;10:856-69.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tlymphocytes in hepatocellular carcinoma immune microenvironment:Insights into human immunology and immunotherapy. Am J Cancer Res. 2020;10:4585-606.

- [Google Scholar]

- Progression on the roles and mechanisms of tumor-infiltrating T lymphocytes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Immunol. 2021;12:729705.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pathologic definition and number of lymphovascular emboli:Impact on lymph node metastasis in endoscopically resected early gastric cancer. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2132-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Vascular invasion affects survival in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Mol Clin Oncol. 2015;3:252-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- The role of lymphovascular invasion as a prognostic factor in patients with lymph node-positive operable invasive breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2011;14:198-203.

- [Google Scholar]

- Lymphovascular invasion has a significant prognostic impact in patients with early breast cancer, results from a large, national, multicenter, retrospective cohort study. ESMO Open. 2021;6:100316.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor necrosis in hepatocellular carcinoma-unfairly overlooked? Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28:600-1.

- [Google Scholar]

- Tumor necrosis as a poor prognostic predictor on postoperative survival of patients with solitary small hepatocellular carcinoma. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:607.

- [Google Scholar]

- Substantial risk of recurrence even after 5 recurrence-free years in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2020;26:516-28.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prediction of early recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection using digital pathology images assessed by machine learning. Mod Pathol. 2021;34:417-25.

- [Google Scholar]