Translate this page into:

Registered Dietitians’ enteral feeding practices, obstacles, and needs during the management of critically Ill hospitalized patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: A qualitative study

Address for correspondence: Rabaa A. Alyumni, Clinical Dietitian, MS, Department of Community Health Sciences, College of Applied Medical Sciences, King Saud University, Riyadh 11433, Saudi Arabia. E-mail: rabaa.abdulaziz@hotmail.com

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Qassim Uninversity and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objectives:

Nutritional protocols and guidelines are essential to guide health-care practitioners toward effective enteral feeding management for critically ill patients. Despite the wide availability of international guidelines to direct enteral feeding practices, there are no nutritional guidelines regarding enteral feeding practices tailored for the Saudi Arabian population. In addition, different enteral feeding practices may result in negative outcomes like malnutrition.

Methods:

A qualitative study was conducted through multiple focus group sessions. Pre-formulated structured open-ended questions were asked from the participants during the focus group sessions to gain an in-depth understanding of the current enteral feeding practices. All sessions were audio-recorded, and the transcript was coded and cross-validated.

Results:

A total of five focus group sessions were conducted until data saturation was reached. Data saturation was reached when no additional information was mentioned in the fifth focus group session when compared to all previous sessions. All 24 participants were specialized in the clinical nutrition field with enteral feeding experience in critically ill patients and working in Riyadh city. Twelve themes of the current practices, four themes of obstacles, and four themes of needs were identified with subthemes.

Conclusion:

This qualitative study shows different enteral feeding practices, obstacles, and needs among registered dietitians. Thus, the need for developing national nutritional guidelines tailored to local population characteristics is highlighted. National guidelines are recommended to be compatible with a defined registered dietitian role with clear standards of practices and responsibility for each discipline to achieve a competent health care service.

Keywords

Critical illness

critically ill

enteral feeding

enteral nutritional therapy

guidelines

malnutrition

nutritional practices

nutritional support

protocols

Introduction

Malnutrition is a devastating and highly prevalent condition among hospitalized patients, especially critically ill patients.[1] Nutritional support therapy is one of the approaches that aim to prevent and treat malnutrition and maintain nutritional status within optimum limits.[2]Enteral nutrition (EN) has emerged as the standard method of nutritional support for patients who cannot meet their nutritional requirements orally.[3] However, the hospital setting presents many challenges for providing nutritional support enterally.[3] Thus, careful enteral feeding planning and monitoring are crucial to overcome the challenges and maximize benefits.[3] The patient’s medical status has a considerable influence on enteral feeding practices.[4]

Critical illnesses are associated with stress-related metabolic responses that increase the nutritional risk and complicate the tube-feeding process.[5] The stress-induced metabolic changes lead to higher catabolic rates, systematic inflammation, multiple functional changes in body systems, besides other related complications.[4] Consequently, the EN plan should cautiously address these changes and aim to provide optimum nutritional support, improve the catabolic status, and reduce stress-related complications.[4]

Guidelines and protocols can standardize nutritional practices to improve patients’ nutritional status, reduce hospitalization duration, and save costs.[6] However, the knowledge about nutritional evidence-based practices and interventions is still insufficient.[7] This highlights the need for nutritional guidelines to guide registered dietitians (RD) toward meeting the patient’s nutritional requirements.

Despite the wide availability of international guidelines to direct EN practices, no recommendations or guidelines tailored for the unique healthcare environment across Asia-Pacific and Middle East regions, including Saudi Arabia.[8] Furthermore, a recent systematic scoping review has shown a gap exists between the actual practices and research recommendations.[6] Therefore, specifically tailored local nutritional guidelines are considered important that should be developed and followed by the RDs in their clinical practices. Evidence-based guidelines will improve the quality of care as well as patient’s life, which will be reflected positively in individual health and the overall community.[8]

Methods

This qualitative study aims to investigate the current enteral feeding practices for hospitalized critically ill patients among RDs in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Multiple focus group sessions were conducted to gain an in-depth understanding of the current enteral feeding practices and discover the RDs’ needs and obstacles during their enteral feeding practices. The ethical approval (NO. E-20-5314) for this study has been attained from the Research Ethics Committee at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH).

Participants were recruited through a purposive sampling approach, which enables the selection of participants according to their knowledge and experience of handling and practicing enteral feeding with critically ill patients. The recruitment of the participants was through an invitation link sent to them with some questions regarding demographic information. The questions include gender, years of experience, enteral feeding practices with critically ill patients, workplace, national and international accreditation, educational level, RD title, and the Saudi Commission for Health Specialties (SCFHS) registration number.

The inclusion criteria were RDs in Riyadh city and a minimum of one-year of clinical experience, including practicing enteral feeding with critically ill patients. While the exclusion criteria were RDs from outside Riyadh city and RDs with no enteral feeding experience or less than one-year clinical experience.

The signature on the consent form was received from participates. The focus group sessions were performed through (Zoom communications platform) an online private room. All sessions were audio-recorded and kept in a secure device with limited access to the researchers only to facilitate data analysis. To encourage self-disclosure, participants were divided into five groups with considering differences in the following: years of experience, gender, educational level, and workplace in each group. The moderators of the focus group sessions had training in moderating the focus group sessions via pre-rehearsal sessions.

The key questions of the focus group were formulated based on the researchers’ clinical experience and international guidelines’ reflection such as ASPEN.[9] Each session lasted for around 60–90 min. The focus group sessions were conducted until we reached data saturation.

Participants were expressed in codes, and the audio-recorded sessions were transcribed for data analysis. The transcription was performed manually by the moderator and one assistant. Themes were identified by two independent researchers who were not involved in focus group sessions. The agreement of the identified themes was evaluated manually.

Results

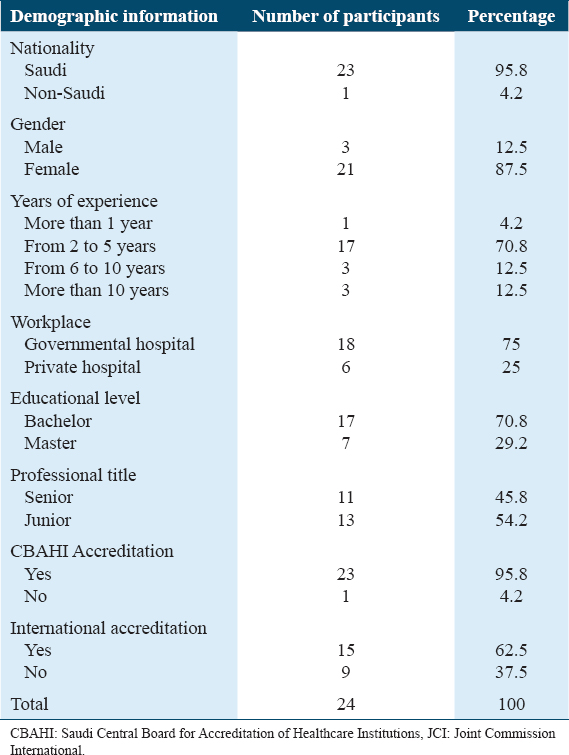

Twenty-four participants working in Riyadh city were involved in five focus group sessions [Table 1].

The focus group sessions were conducted from February to March 2021 until data saturation was reached. In the Fifth focus group session, no additional information was mentioned compared to all previous sessions. Twelve themes were recognized from the current practices, which include: evidence-based guidelines or protocol, medical records and screening tools, eligibility criteria for enteral feeding, enteral feeding timing and initiation, enteral feeding access site and delivery route, nutritional requirements, enteral feeding ordering chain, formula preparation and labeling system, safety precautions to avoid overfeeding and aspiration, monitoring aspects and frequency, the transition from enteral to oral feeding and evaluating food intake, and discharge plan of care.

Furthermore, four themes were documented regarding the obstacles, which include: lack of evidence-based guidelines and protocol, lack of clear RD role and poor communication, lack of follow-up after discharge, and lack of availability or/and preparation of the formula. In addition, four other themes are highlighted regarding the current RD needs, which include: national evidence-based guidelines and protocol, clear RD role, follow-up after discharge, and accurate preparation of the formula. The themes that were identified were divided into subthemes with participants’ comments and quotes [Table 2].

Themes Regarding the Dietitian’s Enteral Feeding Practices During Their Management of Critically Ill Patients are:

Theme 1: Evidence-based guideline or protocol. This theme was divided into three subthemes: guideline or protocol based on internal diligence, adopted international guideline or protocol, and not following specific guidelines or protocol.

Theme 2: Medical records and screening tools. This theme was divided into six subthemes: SOAP note, ADIME note, manual (not predesigned) notes, no screening tools, created screening tool, and adopted an internationally validated screening tool.

Theme 3: Eligibility criteria for enteral feeding. This theme was divided into two subthemes: withier no criteria based on dietitian’s judgement or there is a criterion.

Theme 4: Enteral feeding timing and initiation. This theme was divided into two subthemes: either following a clear protocol for timing and initiation or not following a protocol for timing and initiation.

Theme 5: Enteral feeding access site and delivery route. This theme was divided into two subthemes: no clear role for the dietitian and it is based on the doctor decision and there is protocol and critically ill patients are usually on continuous feeding by doctor’s order.

Theme 6: Nutritional requirements. This theme was divided into two subthemes: no protocol and based on dietitian judgment or there is a protocol based on internal diligence.

Theme 7: Enteral feeding ordering chain. This theme was divided into two subthemes: recommended by the dietitian and should be approved by the doctor first to be effective and direct by the dietitian.

Theme 8: Formula preparation and labeling system. This theme was divided into three subthemes: nor special room with safety precaution for formula preparation neither labeling system, there is a special room without safety precaution for formula preparation and no labeling system, and there are a special room supervised by diet technician with safety precaution for formula preparation and labeling.

Theme 9: Safety precautions to avoid overfeeding and aspiration. This theme was divided into three subthemes: no protocol, dietitian has no role only doctors, there is a protocol for aspiration but not overfeeding, and there is a protocol for aspiration and overfeeding.

Theme 10: Monitoring aspects and frequency. This theme was divided into four subthemes: no protocol based on internal diligence (clinical nutrition department), 2–3 days (labs, weight, tolerance), 3–5 days (labs, weight, tolerance), and no protocol, patients seen on daily bases.

Theme 11: Transition from enteral to oral feeding and evaluating food intake. This theme was divided into four subthemes: no protocol and dietitian have no role, there is a protocol, and it is based on dietitian recommendation, no evaluation for food intake, and dietitians use calorie count.

Theme 12: Discharge plan of care. This theme was divided into three subthemes: no protocol, based on internal diligence (clinical nutrition department), there is a protocol for 1 to 2 weeks, and provide education.

Themes Regarding the Dietitian’s Enteral Feeding Obstacles During Their Management of Critically Ill Patients are:

Theme 1: Lack of evidence-based guidelines and protocol. This theme was divided into two subthemes: no protocols in all current practices based on internal diligence and few protocols in some current practices based on international guidelines.

Theme 2: Lack of clear dietitian’s role and poor interdisciplinary team communication. This theme was divided into five subthemes: absence of dietitian’s role, dietitian only recommending plan, dietitian not working in a multidisciplinary team, low medical team awareness of dietitian role, and delay may occur.

Theme 3: Lack of follow-up after discharge. This theme with only one subtheme which is, some discharged patients are not following feeding recommendations.

Theme 4: Lack of availability or/and preparation of the formula. This theme was divided into two subthemes: not having a special room equipped with the necessary tools to prepare formula safety and accurately and formula shortage.

Themes Regarding the Dietitian’s Enteral Feeding Needs During Their Management of Critically Ill Patients are:

Theme 1: National evidence-based guideline and protocol. This theme was divided into five subthemes: merging current practices with international guidelines, having local nutrient reference value, having national expert panel, personalized plan sometimes needed, and having local primary research.

Theme 2: Clear dietitian role. This theme was divided into two subthemes: orders should come from dietitian and working in a multidisciplinary manner with clearly defined roles and responsibilities.

Theme 3: Follow-up after discharge. This theme with only one subtheme which is, the dietitian should follow-up patient after discharge.

Theme 4: Accurate preparation of the formula. This theme was divided into two subthemes: having a special room for formula preparation supervised by specialized personnel and having enough supplies.

Discussion

Participants frequently reported no specific or clear criteria regarding the eligibility of patients indicated for enteral feeding, and it is based on RD’s judgment. In addition, most of the participants declared that they do not have a clear protocol for enteral feeding timing and initiation in critical settings. Furthermore, most participants reported that it is based on the physician’s decision regarding the access site. In contrast, most participants agreed that critically ill patients usually started with continuous feeding unless other indications. The main obstacles that participants were facing were the lack of clear protocols to guide the RD during enteral feeding practices and low awareness of the RD’s role in the multidisciplinary team, especially in their ordering communication channel. Poor communication between the multidisciplinary team and lack of the RD’s ordering privileges may negatively impact and delays the ordering time of nutritional intervention.[10]Additionally, almost all participants agreed that national guidelines and protocols based on our population characteristics, are highly needed.

Most of the focus group participants emphasized on adoption of international guidelines in their enteral feeding practices. This is in line with the standards of ASPEN and ESPEN guidelines in enteral feeding practices in critically ill patients for RD.[9,11] However, adopting international guidelines does not mean that it is being followed and applied by the RD’s practices since it is not mandatory, and hospitals are not implementing it as claimed by a few of the participants in the focus groups. A retrospective review found that adopting international guidelines with inadequate compliance and implementation resulted in ineffective outcomes.[12,13]This highlights the need for effective monitoring and surveillance for the actual implementation; otherwise, there will be no effective patient outcome for neither adopted international guidelines nor created policy.[12,13]

One of the obstacles highlighted by some participants was the lack of clear protocols and guidelines to guide the RDs in their enteral feeding practices. Additionally, almost all participants mentioned the essential need for national guidelines and protocols tailored and designed based on the local population characteristics, including special calculations, formulas, and nutrient reference values. In addition, a few of them suggested that the development of national guidelines could be developed by national experts panel from different institutions to adequately address the needs. Specifically tailored guidelines will greatly enhance the facilities toward an appropriate and effective intervention to improve the outcomes of enteral feeding practices.[9,14]

In addition, most of the participants reported no specific and clear criteria for identifying eligible patients for enteral feeding. Having a clear criterion or protocol for detecting eligible patients for enteral feeding is an important aspect of comprehensive nutritional therapy, especially for critically ill patients.[11]As revealed by a prospective study that aimed to assess whether nutrition support criteria could improve the nutritional support for critically ill patients. They clarify that having clear criteria for an eligible patient to start with enteral feeding and support resulted positively in respect to an effective nutrients delivery and rapid increment of enteral feeding delivery, which contribute to adequately meeting the nutritional needs and requirements for critically ill patients.[15]

Although half of the participants declare that they have a protocol concerning enteral feeding timing and initiation, they mentioned that it is not usually followed. The included participants have greatly noticed huge differences in the current practices. Following a clear protocol regarding enteral feeding timing and intuition is one of the essential elements of providing an effective EN therapy plan.[11]As evidenced by a recent cross-sectional study that protocols when followed by RD will be reflected positively on patient’s outcomes. This includes meeting the patient’s nutritional requirements and improving gastrointestinal tolerance through EN therapy.[16]

Furthermore, a survey conducted to gain an overview of the current practices of enteral feeding for adult patients in intensive care units found variation among European intensive care units in enteral feeding practices. This study revealed that many intensive care units’ practices do not adopt an international guideline for enteral feeding. In addition, using a nutritional screening tool will lead to an effective nutritional assessment, resulting in benefits from intensive care units’ outcomes. They highlighted that monitoring the enteral feeding practices parallel with adopting an evidence-based guidelines developed by a multidisciplinary professional team will certify an appropriate, safe, and efficient management of critically ill patients receiving enteral feeding. Hence, they conclude that the need for identifying a scope regarding the current practices to develop an evidence-based guideline for enteral feeding practices is essential for European intensive care units. This will greatly enhance facilities toward tailoring appropriate intervention to improve enteral feeding practices.[9,14]

Furthermore, a previous review study aimed to assess enteral feeding practices in critically ill patients. They found contradictory practices for managing ICU patients regarding determining the optimal initiation time for enteral feeding, estimation of nutritional requirements, and choosing suitable formulas were noticed. However, in critically ill patients, severely malnourished cases are considered a major issue due to the associated severe illnesses, severe catabolic state, and stress. Thus, standardizing the enteral feeding practices is considered an important aspect in addressing and managing a patient’s critical condition appropriately.[17]

On the other hand, most participants stated that the physician must approve the RD’s orders first to be effective, which is in line with CBAHI standards.[18] However, they mentioned an obstacle regarding this matter: waiting for the physician’s approval may delay their orders and negatively affect enteral feeding delivery. They highlighted the essential needs for giving RDs the order privilege to improve feeding delivery. As evidenced by a recent retrospective study that aimed to measure the effectiveness of providing RD writing orders privileges for enteral feeding administration in critical care units and to be effective directly without the physician’s approval. They found that a significant improvement in protein delivery in ICU patients. Since adequate nutritional support is allied positively with patient’s improvement and outcomes during critical illnesses, effectively accelerating the nutritional care plan implementation will contribute toward positive outcomes.[19]

Furthermore, the participants also mentioned the lack of a clear RD’s role and poor interdisciplinary team communication as an obstacle. In addition, they reported the need for clarifying the RD’s role for each member in the multidisciplinary team. As illustrated and recommended by ASPEN guidelines, a structured nutritional support service must include RD, physician, nurse, and pharmacist. Each member of the multidisciplinary team must be aware of each member’s role and follow clear standards of practices and responsibility for each discipline to achieve a competent health care service.[20]

Concerning discharge plan of care, focus group participants reported differences in their practices of performing the discharge plan of care. Moreover, few of them reported the absence of follow-up after a patient’s discharge as an obstacle they faced. Besides, they draw attention to the need to follow up with enteral feeding patients after discharge to ensure adequate feeding intake. However, a recent narrative review revealed that post ICU discharge plan of care is essential to reduce the possibility of patients from becoming a “victim” of delayed recovery due to inadequate nutrients intake. Additionally, according to CBAHI standards and JCI policy, an individualized discharge plan of care must be established and prescribed to ensure and maintain nutritional targets and continuing enteral feeding tolerance post-ICU discharge.[9,18,21-23]

Regarding the formula preparation and labeling system, some participants during the focus group discussion declared the lack of an appropriate and special room with safety precautions for preparing EN formulas and without formulas labeling. However, according to ASPEN safe practices guidelines for EN, emphasized the importance of safe formula preparation room with labeling system.[9,20,24] A recent review highlighted that ICU patients are at higher risk of infection when compared to other patients due to their condition of immunocompromised situation. Thus, EN formulas when prepared at patient’s bedside or kitchen without safety precautions may increase the risk of contamination. Contaminated EN formulas might contribute to gastrointestinal disturbance, feeding intolerance, and morbidity.[25] Furthermore, EN’s formula should be labeled with the formula’s content, patient’s name, and medical record number with clear indication that formula is intended for tube feeding administration.[10]This appropriate practice during the management of enterally fed critically ill patients should be adopted in order to reduce the risk ofcontamination, improve the nutrition delivery to patients, and to make this intervention safe for ICU patients.[25]

Those different practices, obstacles, and needs were noticed, increasing the demand to develop national nutritional guidelines and protocols tailored to local population characteristics. This study identified the gaps compared to international guidelines and protocols, which may help in building evidence-based guidelines for enteral feeding in Saudi hospitals.

Strengths and limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first study that identified the current clinical dietitian’s practice of enteral feeding during the management of critically ill patients in Riyadh’s hospitals and identify the practitioner’s needs and obstacles. However, the generalizability of the study’s results is limited. Further local primary research is needed to clarify the evidence.

Conclusion and Recommendations

To conclude, critically ill patients are at high risk of being malnourished due to stress-related metabolic responses and higher catabolic rates. However, differences in enteral feeding practices in different Saudi hospital settings have been noticed. The essential needs for local primary research and nutrients reference values are important to develop national evidence-based guidelines and protocols which are greatly highlighted. Evidence-based guidelines will help decision-makers standardize a protocol for enteral feeding in Saudi hospitals, which will benefit local accreditation agencies for quality assurance purposes. Developing unified national protocol and guidelines, including clear protocol for follow-up critically ill patients upon discharge and a special formula preparation room equipped with appropriate tools and trained personnel, will result in more homogeneous practices. This qualitative study shows different enteral feeding practices, obstacles, and needs among registered dietitians. Thus, the need for developing national nutritional guidelines tailored to local population characteristics is highlighted. According to the Saudi Standard Classification of Educational Specialties and Occupations, RD’s have defined clear roles. One of the main RD’s roles is to provide EN therapy care plan for critically ill patients.[16,26,27] It is recommended that all concerned institutions and sectors, including educational, training, and practical institutions to modify their standards, protocols, and competencies accordingly. The national guidelines should be compatible with the defined RD’s role with clear standards of practices and responsibilities for each discipline in order to achieve a competent health care service. Standardizing the RD’s enteral feeding practices will be reflected positively on improvingpatient’s health outcomes by enhancing their nutritional status. In addition, it will assist in reducing the cost burden on governmental health institutions by cutting budgets and shortening the possible length of stay.

Authors Declaration

Ethical approval and consent to participants

The Research Ethics Committee at King Khalid University Hospital (KKUH) approved this study (NO. E-20-5314). In addition, a signed consent form was obtained from participants before the beginning of focus group sessions.

Data availability statement

The audio-recorded data that supports the findings of this study are not publicly available since it contains information that could compromise the privacy and identity of research participants. However, other needed data and information are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Funding sources

No funding was received for this research.

Author’s Contributions

RabaaAlyumni: research conception, methodology, formulating structured questions for focus groups, participate in data collection of focus groups, data analysis with theming, and writing manuscript. Khalid Aldubayan: research conception, methodology, formulating structured questions for focus groups, participate in data collection of focus groups, data validation (testing agreement), and review manuscript. Fatimah Alsoqeah: research conception, methodology, formulating structured questions for focus groups, and participate in data collection of focus groups. NawafAlruwaili: formulating structured questions for focus groups, data validation (testing agreement), and review manuscript.

Acknowledgements

None.

References

- Prevalence of malnutrition in hospitalized patients:A multicenter cross-sectional study. J Korean Med Sci. 2018;33:e10.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2017. Nutrition Support for Adults:Oral Nutrition Support, Enteral Tube Feeding and Parenteral Nutrition. London: National Collaborating Centre for Acute Care (UK); Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg32

- Enteral nutrition for adults in the hospital setting. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30:634-51.

- [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic response to the stress of critical illness. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:945-54.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evidence on nutritional therapy practice guidelines and implementation in adult critically ill patients:A systematic scoping review. Curationis. 2019;42:e1-13.

- [Google Scholar]

- Experiences of health professionals with nutritional support of critically ill patients in tertiary hospitals in Malawi. Malawi Med J. 2015;27:1-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutrition therapy for critically ill patients across the Asia-Pacific and Middle East regions:A consensus statement. Clin Nutr ESPEN. 2018;24:156-64.

- [Google Scholar]

- ASPEN safe practices for enteral nutrition therapy [Formula:See text. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2017;41:15-103.

- [Google Scholar]

- A qualitative study investigating the current practices, obstacles, and needs of enteral nutrition support among registered dietitians managing non-critically ill hospitalized patients in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Syst Res. 2023;3:10-22.

- [Google Scholar]

- ESPEN guideline on clinical nutrition in the intensive care unit. Clin Nutr. 2019;38:48-79.

- [Google Scholar]

- Early enteral nutrition in burns:Compliance with guidelines and associated outcomes in a multicenter study. J Burn Care Res. 2011;32:104-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Compliance with nutrition support guidelines in acutely burned patients. Burns. 2012;38:645-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- A European survey of enteral nutrition practices and procedures in adult intensive care units. J Clin Nurs. 2007;16:2132-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutrition of the critically ill patient and effects of implementing a nutritional support algorithm in ICU. J Clin Nurs. 2006;15:168-77.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians'perceptions of Dietitians'services and roles in Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Saudi J Health Syst Res. 2023;3:10-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Enteral nutrition in intensive care patients:A practical approach. Working Group on Nutrition and Metabolism, ESICM. European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1998;24:848-59.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2018. Introduction to the Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions. Available from: https://portal.cbahi.gov.sa/english/cbahi-standards

- Effect of registered dietitian nutritionist order-writing privileges on enteral nutrition administration in selected intensive care units. Nutr Clin Pract. 2019;34:899-905.

- [Google Scholar]

- Standards for nutrition support:Adult hospitalized patients. Nutr Clin Pract. 2018;33:906-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nutrition therapy and critical illness:Practical guidance for the ICU, post-ICU, and long-term convalescence phases. Crit Care. 2019;23:368.

- [Google Scholar]

- Critical analysis of patient and family rights in JCI accreditation and CBAHI standards for Hospitals. Int J Emerg Res Manag Technol. 2018;6:324.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2013. Accredited Standards Organizations. Available from: https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/jci-accredited-organizations

- Early versus delayed enteral nutrition in mechanically ventilated patients with circulatory shock:A nested cohort analysis of an international multicenter, pragmatic clinical trial. J Crit Care. 2022;26:173.

- [Google Scholar]

- Safety of enteral nutrition practices:Overcoming the contamination challenges. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2020;24:709-12.

- [Google Scholar]

- Physicians'knowledge of clinical nutrition discipline in Riyadh Saudi Arabia. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1721.

- [Google Scholar]

- 2020. Saudi standards Classification of Educational Specialties and Occupation Ministry of Education. Available from: https://apsp.qu.edu.sa/files/shares/دليل-التصنيف-السعودي-الموحد للمستويات-التعليمية.pdf