Translate this page into:

Smoking cessation interventions in patients diagnosed with head and neck cancers: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials

Address for correspondence: Dr. Rahul N. Gaikwad, Department of Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, College of Dentistry, Qassim University, Buraydah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. E-mail: r.gaikwad@qu.edu.sa

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 Unported, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

This article was originally published by Qassim Uninversity and was migrated to Scientific Scholar after the change of Publisher.

Abstract

Objective:

According to findings from the previous studies, quitting smoking can significantly reduce mortality from all causes and is linked to better treatment results. Even though quitting smoking has many benefits, little is known about the evidence supporting the particular quit services offered to smokers after a cancer diagnosis.

Methods:

To find the articles related to area in question, different electronic databases including PubMed/Medline, Google Scholar, and EBSCO were searched on April 1st, 2023. All full text randomized controlled trials with one or more intervention and control groups that assessed the outcomes of smoking cessation interventions were included. Participants of included studies were adults diagnosed with head and neck cancer (HNC) and current smokers or those who had recently quit. There were interventions (pharmacological and/or pharmacological) that aimed to help patients with HNC succeed in quitting smoking.

Results:

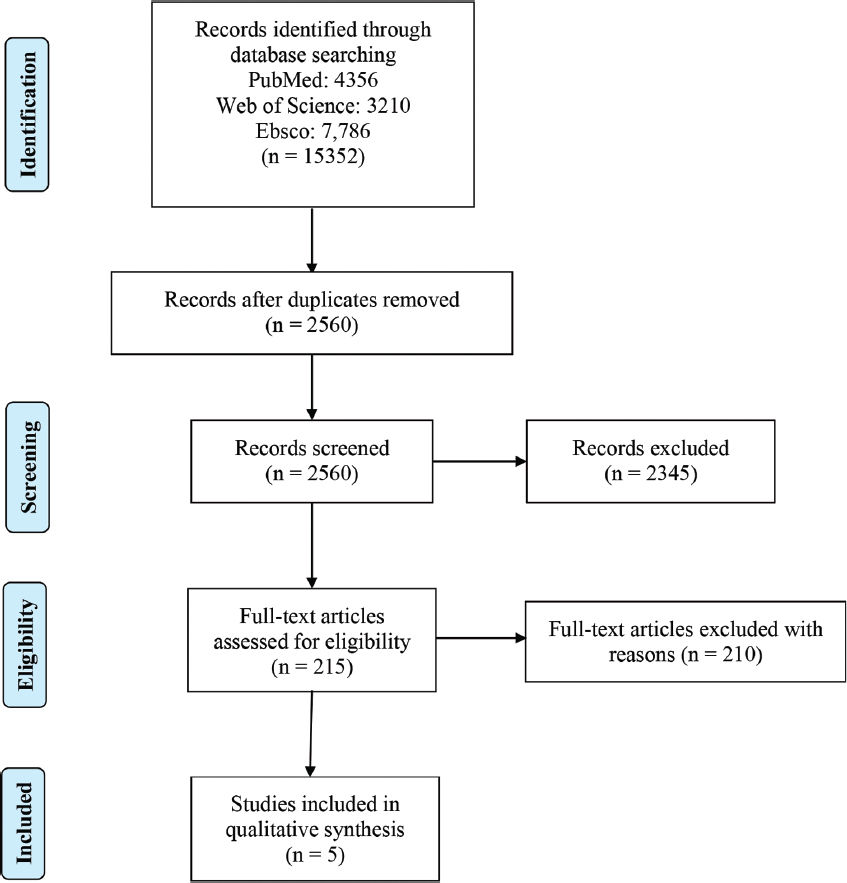

We identified 15352 papers from the initial search from different electronic databases, 2560 remained after excluding duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts for relevance, 2345 articles were removed. Full text articles of remaining 215 papers were assessed in depth by two reviewers for their eligibility, amongst which, 210 articles were excluded. Finally, we included five papers that met the inclusion criteria in the present systematic review.

Conclusion:

According to the findings of this review, a multi - component strategy might very well benefit patients with HNC who smoke cigarettes after diagnosis. More studies with high methodological quality and standardized outcome measures must be conducted in this population to inform the development of smoking cessation program.

Keywords

Head and neck cancer

oral cancer

smoking cessation

tobacco cessation intervention

Introduction

It is beyond dispute that smoking has a negative impact on one’s health and happiness. More importantly, smoking and tobacco use are major risk factors for head and neck cancer (HNC),[1] with tobacco and alcohol use being linked to more than 75% of cases of this cancer.[2] Nevertheless, many people who have been diagnosed with cancer continue to smoke.[3,4] Continued smoking raises the risk of developing additional smoking-related diseases, developing a second primary tumor, experiencing a recurrence of the disease, experiencing a reduction in the treatment’s efficacy, experiencing increased radiation therapy toxic effects and side effects, and having a lower chance of overall survival.[5-7] Within 2–3 years of the initial cancer diagnosis, 10–12% of HNC patients experience a second HNC.[8]

According to findings from previous studies, quitting smoking can significantly reduce mortality from all causes and is linked to better treatment results. This is true even after a cancer diagnosis has been made.[9] It is clear that giving up smoking is linked to a two-fold increase in complete response to radiotherapy in patients with locally advanced HNC.[5] Quitting smoking has also been linked to improved performance status, lower levels of pain, and higher quality of life (QOL) scores in cancer patients.[10] In addition, ceasing to smoke after diagnosis lowers morbidity and mortality,[5,11] especially in people with smoking-related cancers like HNC and those with diseases that are treatable.[12]

Reducing tobacco use in high-risk populations remains a challenge. To support the engagement of health-care professionals and better comprehend their perceived challenges, Keyworth et al.[13] offer reported that more support is required for training in quitting tobacco. Although high intensity, multicomponent interventions with a mix of pharmacological and behavioral approaches have been found to be effective in improving cessation rates in the general oncology population by systematic reviews of smoking cessation interventions.[14,15] Patients with a higher risk of developing cancer have been found to react differently to treatments that aim to help them quit smoking based on how significant their tobacco use is thought to be in either the progression or treatment of the disease.[16] In addition, patients diagnosed with HNC may experience gastrointestinal issues, mucositis, dry mouth, and changes in taste depending on the location of the tumor and the treatment that is administered for it.[17] which may specifically affect a patient’s receptivity to specific pharmacotherapy interventions like nicotine gum, and therefore necessitate a customized approach to smoking cessation therapy. Even though quitting smoking has many benefits, little is known about the evidence supporting the particular quit services offered to smokers after a cancer diagnosis.

Therefore, the objective of this systematic review was to pinpoint smoking cessation strategies and their effects for people with HNC in randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Methods

The preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (PRISMA) statement’s instructions were followed when conducting the current systematic review Table S1.

A focused PICO question

PICO question was defined for screening the qualified studies: “does the type of tobacco cessation intervention can affect quit rate? (1) Population: Patient diagnosed with HNC; (2) Intervention: Pharmacological and non-pharmacological intervention; (3) Comparison: Conventional counseling; and (4) Outcome: Rate of tobacco quitting.

Search strategy

Different electronic databases including PubMed/Medline, Google Scholar, and EBSCO were searched on April 1, 2023. To find the omitted articles, the references list of all the pertinent papers were carefully examined. The following key words were used tobacco cessation, tobacco cessation intervention, tobacco quit, oral cancer, and HNC.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

All full text RCTs with one or more intervention and control groups that assessed the outcomes of smoking cessation interventions were included. Participants of included studies were adults diagnosed with HNC and current smokers or those who had recently quit. There were no restrictions on type or stage of treatment. There were interventions that aimed to help patients with HNC succeed in quitting smoking. Non-pharmacological and/or pharmacological components may be used in interventions. No limitations were placed on the study’s sample size, participant gender, study country, publication date, or language. The following criteria excluded from the study were any parallel comparison or control groups. In present review, we did not apply any limitation for publication date or the length of the follow-up. Reviews, case studies, commentary, letters to the editor, books, and unpublished articles were not included. Studies that looked at smoking cessation for caregivers of HNC patients were also disregarded.

Study selection

To find pertinent papers, two authors (RG and FA) first performed a preliminary screening of the titles and abstracts. After recognizing and further evaluating the full texts of all potentially qualified papers, studies that satisfy all inclusion criteria were found. A list of the research papers to be included in this review was finally confirmed, and any disagreements were settled through discussion with a third author.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed and modified from previous documents used by authors (MA and FA) Two authors independently evaluated each of the chosen RCTs to extract data such as country, year of publication, first author study setting, study design, description of the intervention, number and characteristics of participant outcome measures, outcomes, and follow-up duration. Any uncertainties observed were discussed and resolved in the consensus meetings with all the authors.

Quality assessment

All included reports underwent a systematic review using the critical appraisal skills program checklist, which evaluated the quality of each one. Regarding application and time, the tool is simple to use and has a satisfactory level of validity. The three authors independently evaluated the study’s quality. Any discrepancies between the two reviewing authors were discussed in order to resolve them, and the third author was brought in to resolve disputes when necessary.[18]

Data analysis

A meta-analysis could not be performed due to the included studies’ significant heterogeneity as revealed by data extraction. Instead, information was combined into a table and a descriptive summary was created to describe the nature and results of the study.

Results

Figure 1 shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the literature search and results. We identified 15352 papers from the initial search from different electronic databases (PubMed: 4356, Web of Science: 3210, Ebsco: 7,786) and 2560 remained after excluding duplicates. After screening titles and abstracts for relevance, 2345 articles were removed. Full text articles of remaining 215 papers were assessed in depth by two reviewers (Mujahid and FA) for their eligibility, among which, 210 articles were excluded. Finally, we included five papers[19-23] that met the inclusion criteria in the present systematic review.

- PRISMA flowchart for the study selection

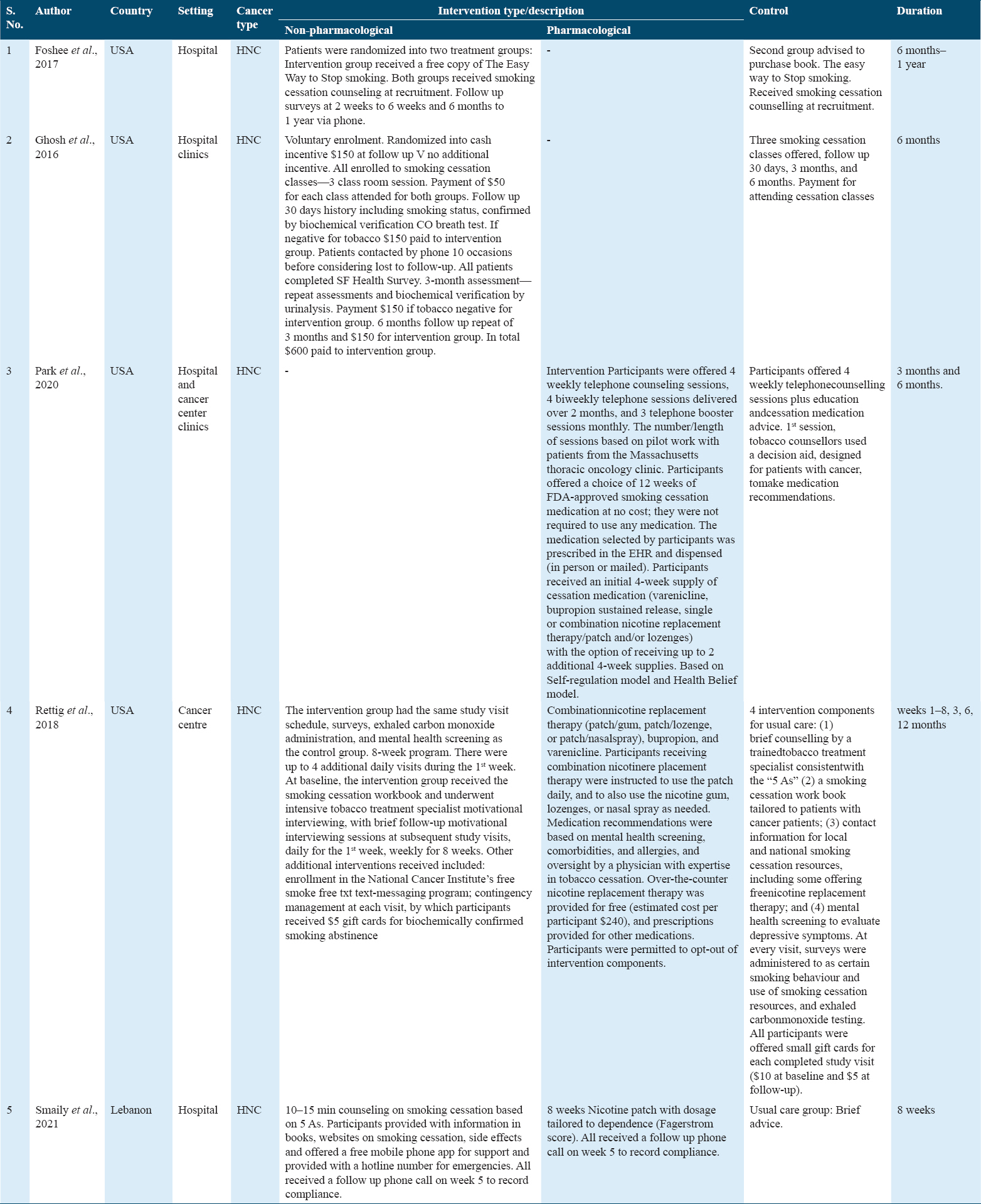

Study characteristics

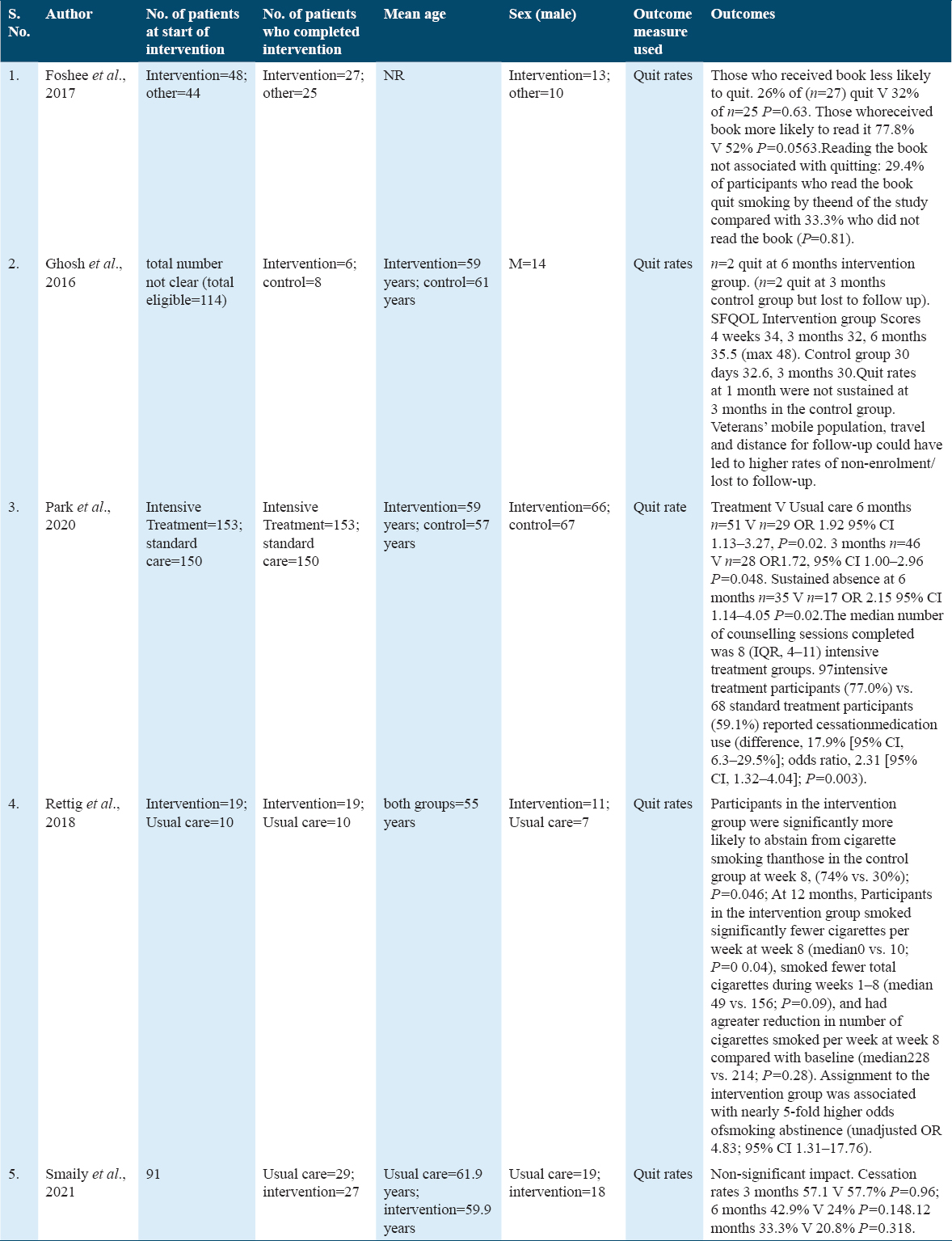

The detailed characteristics of all included studies are given in Tables 1 and 2. Geographically, among five studies, four trials were conducted in USA[19-22] and remaining one trial was carried out in Lebanon.[23] All trials included data that report interventions for smokers diagnosed with HNC. Included studies were published between 2016 and 2021. In every trial, the intervention was compared to a usual care, no intervention, control. The interventions employed in all trials targeted smoking cessation alone, except for trial by Rettig et al.[22] in which mental health of control group participants was screened to evaluate depressive symptoms. The trials’ interventions range in follow-up time from 1 month to 12 months. Most patients who are hospital inpatients or who visit cancer clinics or centers are recruited for studies and programs.

Participants in the trials ranged in age from 29 to 303. Healthcare professionals delivered smoking cessation interventions that were either non-pharmacological on their own (self-help books, website content and publications, and telephone counseling), or combined with a pharmacological element (nicotine replacement therapy, varenicline, or bupropion). National mobile phone apps were included in the hospital-based smoking cessation programs created by Rettig et al.[22] According to two studies, varenicline and pharmacotherapies to aid in quitting are either free or inexpensive.[21,22] Money-related incentives were also mentioned.[20,22] In every trial, the control group received standard care, which could have included anything from counseling on the dangers of continuing to smoke to the advantages of quitting, to resources for quitting, to payment/small gift cards for attending classes [Table 1].

The intervention outcomes for the included trails are described in Table 2. Results of smoking cessation were reported in each of the five included trails. Rettig et al.[22] reported higher quit rates in the married group who were in the intervention group OR 4.83, 95% CI 1.31–17.76. Three trials reported the impact on quit rates.[21-23] Patients with a history of depression, co-addictions, and mucositis were found to have lower odds of quitting. Increased smoking rates were linked to higher pain and mucositis scores. According to Rettig et al.,[22] incorporating smoking support services into cancer treatment has benefits. According to Park et al.,[21] more counseling sessions — n = 8 IQR 4 to 11 — were linked to the use of stop pharmacotherapies in the treatment group compared to usual care (77.0% compared to 59.1%); OR 2.31 95% CI, 1.32-4.04; P = 0.003. Similarly et al.[23] observed a negligible impact, though. Cessation rates at 3 months were 57.1 V 57.7%, and at 6 months, 42.9 V 24%, respectively. About 33.3% over a year versus 20.8% P = 0.318.

In their RCT, Foshee et al.[19] gave away copies of the book The Easy Way to Stop Smoking to participants in the intervention group and suggested that those in the control group buy the same book. At recruitment, smoking cessation counseling was provided to both groups. A follow-up phone survey was conducted at 2 weeks, 6 weeks, and 6 months to a year. The authors found that those who received the book had a higher reading rate (77.8%) than those in the control group (52%) with P = 0.0563. Reading the book was not linked to quitting, though: only 29.4% quit tobacco by the end of the study, compared to 33.34% of non-readers (P = 0.81). As a result, authors hypothesized that recipients of books were less likely to give up.

Ghosh et al.[20] in their RCT paid incentives to both groups for attending smoking cessation classes and smoking status was confirmed by biochemical verification; evaluated QOL by SF questionnaire and noticed that 2 out of 6 patients quit the smoking habit. However, other lost to follow-up. SF QOL intervention group scores were for 4 weeks: 34, 3 months: 32, 6 months: 35.5. For the control group, the SF QOL scores were as follows for 30 days: 32.6, 3: months 30. According to authors, participants valued smoking more than any reward for quitting.

Discussion

The objective of the current review was to assess the effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions to increase cessation rates in patients with HNC. There were only five RCTs found in the current review. Only two of these reported appreciable increases in follow-up cessation rates. These findings highlight the dearth of thorough research on smoking cessation interventions among HNC patients, a group in which quitting tobacco use is essential. The range of interventions used in cancer centers included the distribution of fact sheets, the creation of smart phone applications, and connections to national smoking cessation programs. This review covers all aspects of intervention characteristics and their effectiveness or other positive change.

Interventions were provided in each of the five trials by a medical professional who was involved in the care of patients with HNC. In fact, a lot of best practice guidelines recommend that those responsible for cancer patients’ care determine whether the patients smoke and offer them support for quitting. Oncology-related healthcare professionals are in a good position to offer smoking cessation interventions.

The development and use of electronic patient records, as well as documenting patients’ smoking status at each clinical encounter, are among the systems issues that are identified as crucial for supporting smoking cessation programs. The trials that were examined in this review show the variety of methods and the timing of conversations, from visiting cancer centers or clinics to evaluate cancer treatment to planning for/starting treatment to actually receiving treatment for cancer.[19-23]The length of smoking cessation services and conversations offered, as well as the need for knowledge about the impact of continued smoking on cancer recovery, have all been mentioned in the previous literature.[24,25] Conlon et al.[26] recommendation that information about quitting should be emphasize at every stage. The results of this review indicate that pharmacotherapies, increased consultation, counseling, and follow-up reviews are crucial elements of a smoking cessation intervention, as well as the integration of cessation services into cancer care as standard practice.

According to Rettig et al.[22] the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Moonshot initiative includes integrating oncology services. The previous research backs the use of inventions in the oncology setting to help cancer patients and survivors maintain abstinence.[27] However, Frazer et al.[28] systematic review discovered that a number of studies had identified the lack of confidence among health professionals supporting smokers. Feuer’s et al.[29] analysis of 29 studies that looked at smoking relapse in a population of cancer survivors revealed similar results. They claim that smoking cessation following a cancer diagnosis is understudied and that the heterogeneity of interventions makes it difficult to interpret results.

In two of the studies examined for this review, there were significant differences in the outcome of smoking cessation between the intervention and control groups.[21,22] The intervention used in Park et al.[21] study was high intensity and multicomponent, with multiple intermittent telephonic counseling sessions that targeted multiple risk behaviors and combination of nicotine replacement therapy and smoking cessation medications. Rettig et al.[22] also provided combination of nicotine replacement therapy and smoking cessation medications. This finding implies that patients with HNC with long history of heavy smoking respond less as compared to low intensity group[30] This finding is also supported by prior research, which claims that intensive smoking cessation interventions that combine behavioral interventions with medication for quitting smoking maximize the likelihood of a successful long-term outcome.[31,32] However, we firmly believe that future studies comparing the effects of high-intensity, combined behavioral interventions and pharmacotherapy with those of low-intensity, single component interventions on long-term biochemically verified smoking cessation outcomes in patients with HNC are necessary.

Numerous patients with HNC who smoke have a history of binge drinking.[33] Smoking and drinking have been linked to nutritional issues in HNC as a result of the cancer and its treatment. It was evident from the past literature that integrated treatment is effective for coexisting problems in smokers.[14,34] The findings of the present systematic review are in accordance with this. Given the high rate of depression in this population and the link between smoking, alcohol use, and depression, treating the triad as a whole in HNC patients who want to quit smoking may be more beneficial. Therefore, we believe that multicomponent and integrated treatment should be applied wherever is possible.

This review’s strength lies in the fact that it fills a knowledge gap by reporting on the interventions used to aid smokers with HNC in giving up the habit. In addition, we did not limit the size of the evidence we present for this population by excluding studies based on the length of the intervention. The limitations of the review include small sample sizes in all the included trials. The duration of interventions varied in the trials presented with only 8 weeks duration in one trial.[23] Only two studies[20,22] used biochemical verification to confirm that participants had stopped smoking. Research examining the effects of quitting smoking on medical populations at risk for smoking-related diseases should include biochemical verification of smoking status.[35] A critical population of smokers with HNC has been identified, and this review’s systematic approach has revealed the breadth of interventions implemented to date for this group.

Conclusion

The current systematic review found very few RCTs that assessed the efficacy of smoking cessation interventions in HNC patients. According to the findings of this review, a multi - component strategy might very well benefit patients with HNC who smoke cigarettes after diagnosis. There is a ton of room to grow the body of evidence in this field. More studies with high methodological quality and standardized outcome measures must be conducted in this population to inform the creation of smoking cessation programs given the significance of tobacco use as a risk factor for HNC and its impact on treatment outcomes and disease progression. Given the stigma attached to cancer diagnosis and treatment, we believe that when developing and implementing role in supporting tobacco control and smoking cessation in cancer care services, the perspectives of HNC patients should be taken into account.

References

- Head and neck squamous cell cancer and the human papillomavirus:Summary of a National Cancer Institute State of the Science Meeting, November 9-10 2008. Vol 31. Washington, D. C: Head Neck; 2009. p. :1393-422.

- Epidemiology of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma not related to tobacco or alcohol. Curr Opin Oncol. 2013;25:229-34.

- [Google Scholar]

- Atailored smoking, alcohol, and depression intervention for head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2203-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Smoking cessation in patients diagnosed with head and neck cancer. J Otolaryngol. 2004;33:75-81.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of cigarette smoking on the efficacy of radiation therapy in head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:159-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- Influence of smoking cessation after diagnosis of early stage lung cancer on prognosis:Systematic review of observational studies with meta-analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5569.

- [Google Scholar]

- Second cancers following oral and pharyngeal cancer:Patients'characteristics and survival patterns. Eur J Cancer B Oral Oncol. 1994;30B:381-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Smoking cessation after a cancer diagnosis is associated with improved survival. J Thorac Oncol. 2020;15:705-8.

- [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of smoking cessation in subjects with cancer:A 30-year review. Respir Care. 2014;59:1924-36.

- [Google Scholar]

- The effects of a smoking cessation intervention on 14.5-year mortality:A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;142:233-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of long-term smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:261-70.

- [Google Scholar]

- Delivering opportunistic behavior change interventions:A systematic review of systematic reviews. Prev Sci. 2020;21:319-31.

- [Google Scholar]

- Smoking cessation interventions in cancer care:Opportunities for oncology nurses and nurse scientists. Annu Rev Nurs Res. 2009;27:243-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Evaluating smoking cessation interventions and cessation rates in cancer patients:A systematic review and meta-analysis. ISRN Oncol. 2011;2011:849023.

- [Google Scholar]

- Successes and failures of the teachable moment:Smoking cessation in cancer patients. Cancer. 2006;106:17-27.

- [Google Scholar]

- Incidence of weight loss in head and neck cancer patients on commencing radiotherapy treatment at a regional oncology centre. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 1999;8:133-6.

- [Google Scholar]

- Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses:The PRISMA statement. Int J Surg. 2010;8:336-41.

- [Google Scholar]

- Prospective, randomized, controlled trial using best-selling smoking-cessation book. Ear Nose Throat J. 2017;96:258-63.

- [Google Scholar]

- You can't pay me to quit:The failure of financial incentives for smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. J Laryngol Otol. 2016;130:278-83.

- [Google Scholar]

- Effect of Sustained Smoking Cessation Counseling and Provision of Medication vs Shorter-term Counseling and Medication Advice on Smoking Abstinence in Patients Recently Diagnosed With Cancer:A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2020;324:1406-18.

- [Google Scholar]

- Pilot randomized controlled trial of a comprehensive smoking cessation intervention for patients with upper aerodigestive cancer undergoing radiotherapy. Head Neck. 2018;40:1534-47.

- [Google Scholar]

- Smoking cessation intervention for patients with head and neck cancer:A prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Otolaryngol. 2021;42:102832.

- [Google Scholar]

- Predictors of varenicline adherence among cancer patients treated for tobacco dependence and its association with smoking cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21:1135-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Recruiting family dyads facing thoracic cancer surgery:Challenges and lessons learned from a smoking cessation intervention. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2016;20:199-206.

- [Google Scholar]

- Cigarette-smoking characteristics and interest in cessation in patients with head-and-neck cancer. Curr Oncol. 2020;27:e478-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Association of a comprehensive smoking cessation program with smoking abstinence among patients with cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1912251.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic Review of Smoking Cessation Interventions for Smokers Diagnosed with Cancer. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:17010.

- [Google Scholar]

- Systematic review of smoking relapse rates among cancer survivors who quit at the time of cancer diagnosis. Cancer Epidemiol. 2022;80:102237.

- [Google Scholar]

- Nicotine dependence and smoking habits in patients with head and neck cancer. J Bras Pneumol. 2014;40:286-93.

- [Google Scholar]

- Combined pharmacotherapy and behavioural interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD008286.

- [Google Scholar]

- Helping hospital patients quit:What the evidence supports and what guidelines recommend. Prev Med. 2008;46:346-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- Factors affecting smoking cessation in patients with head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:888-92.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy for coexisting depression and alcohol problems:Short-term outcome. Addiction. 2010;105:87-99.

- [Google Scholar]

- Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res.. 2002;4:149-59.

- [Google Scholar]